|

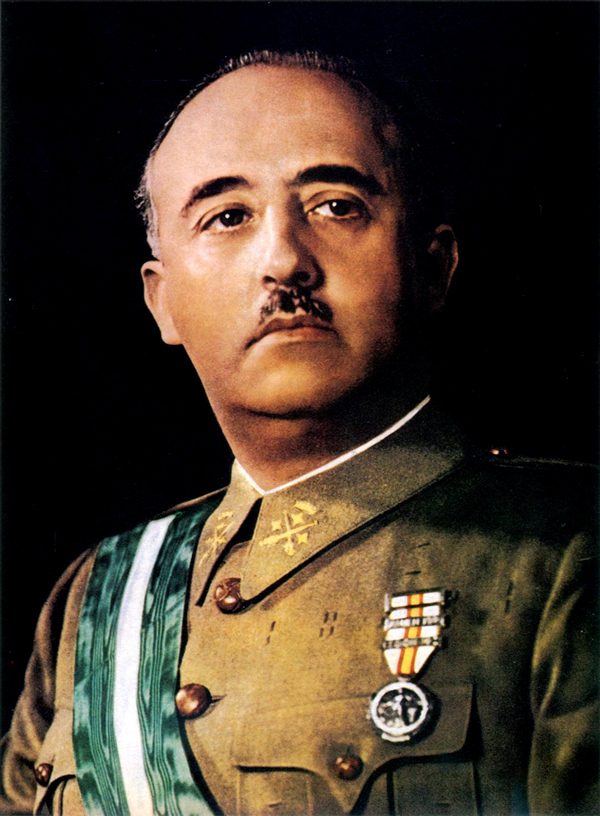

| Francisco Franco |

The man who led the nationalists to victory during the Spanish civil war and governed Spain until his death in 1975, Francisco Franco Bahamonde was the longestserving dictator in Europe in the 20th century, narrowly eclipsing the record set by his neighbor, Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar.

Francisco Franco Bahamonde was born in 1892 in El Ferrol, near Corunna on the Atlantic coast of Spain. It was the country's most important naval base, and his father, Nicolas, worked in the pay corps in the naval arsenal, as had his father before him.

Franco's father was a gambler and drinker, so the upbringing of Francisco Franco and his four siblings was left to their mother, María, who raised the children as devout Roman Catholics.

|

Franco was six when the Spanish-American War broke out, and it was not long before he saw what was left of the once-proud Spanish navy limp back into El Ferrol following the loss of the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. Franco's application to the naval academy was rejected, so he went to the Infantry Training College at the Alcazar in Toledo, near Madrid.

There Franco was initially the smallest boy in his class, but he completed his time there in 1910, the youngest in his graduation year. Commissioned as a lieutenant, he went to Morocco, where he served in the Regulares. This unit, a forerunner of the Spanish foreign legion, was involved in some of the toughest combat against Abd el-Krim.

Promoted to major at the age of 23, Franco was badly wounded in the stomach but miraculously survived. A later account had him threatening to shoot the doctor when the medic decided not to evacuate him because his wound was regarded as too serious.

Returning to Morocco in 1921, Franco led a brilliant action near Melilla, a Spanish-held town on the Mediterranean coast, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel and then gazetted full colonel soon afterward. In October 1923 Franco was asked by King Afonso XIII to escort him when the royal party toured Spanish Morocco.

|

| Generalissimo Francisco Franco reviewing his Falangist troops after taking Madrid in 1939 |

Three years later Franco was promoted by a special decree to the rank of brigadier general, making him, at the age of 33, not only the youngest general in Spain but also the youngest general in Europe since Napoleon.

In 1927 the Spanish finally announced the defeat of Abd el-Krim, and Franco was appointed to head the General Military Academy in Saragossa. The aim of the academy was to create a new Spanish army, and this enabled Franco to inspect a training school at Leipzig.

Franco was courted by the politician Primo de Rivera to stage a coup against King Alfonso XIII, but Franco declined. Primo de Rivera died soon afterward, and when the king visited the academy at Saragossa he publicly embraced Franco and gave the school the right to fly the royal standard. In April 1931 he abdicated the throne, and Spain became a republic.

|

The first elections during the republic saw a leftwing government come to power. The new government wanted to reduce the influence of the army, and one of the leaders of the republic, Manuel Azana, ordered the closure of the Saragossa Academy. In 1932 there was a plan to stage a military coup, but it never happened.

In the following year's elections, a right-wing coalition government was elected. By now Franco's brother-inlaw, Ramón Serrano Súñer, was a rising politician, and he helped Franco in his next assignment.

Opposing the conservative government, 40,000 miners in Asturias in the north of Spain went on strike, and Franco was sent to put down this revolt. He used Moorish soldiers and brutally crushed the miners' revolt—over 1,000 people died, and many more were thrown into prison.

Many Spaniards were worried by the treatment of the miners and also by the rise of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. In February 1936 the elections saw a new left-wing government elected, and the military prepared to stage a coup to bring down this Popular Front government.

The new republican government, worried about Franco, posted him to the Canary Islands. On July 18 Franco was flown to Spanish Morocco, and the army there rose to support him as the generals openly proclaimed their aim to bring down the Spanish government.

With the outbreak of the Spanish civil war the republicans tried to prevent Franco and his men from reaching the Spanish mainland, but an airlift was organized by the Italians and Germans.

Franco then marched his men and their mainland supporters toward Madrid. By the end of July Franco's supporters, the nationalists, controlled a large swath of territory in northern Spain, a pocket around Cádiz, Seville, and Córdoba in the south, and Spanish Morocco.

Franco nearly reached Madrid but diverted his attack to rescue the besieged nationalists at the Alcazar in Toledo. Although this action was highlighted as an "honorable" action in the foreign press, it did allow the republicans to reinforce Madrid and thus prolong the war for another three years.

In October 1936 Franco, by then one of the leading commanders of the rebellion, was proclaimed the supreme commander of the nationalist forces and the chief of state of a nationalist government with its capital at Burgos in northern Spain.

The original leader, General Sanjurjo, had been killed in a plane crash some months earlier. Over the next three years of the war, Franco emerged as a political figure who united his forces into a unified command structure.

The Falange (Spanish fascists), monarchists, Carlists, moderate Catholics, and conservatives put aside their not inconsiderable differences to face the republicans, whose divisions and factional disputes became legendary.

With support from Germany and Italy, Franco's soldiers gradually captured more and more territory from the republicans. Adopting the title caudillo, he portrayed the war as a crusade by which he was to save Spain from Soviet communism, anarchists, and Freemasons. Franco remained a conservative military commander and avoided taking risks.

As a result, he was accused by his own supporters of holding back from delivering a decisive military thrust to allow his men to totally destroy the republicans by attrition. On May 18, 1939, Franco issued his last communiqué of the war, and on the following day he presided over a victory parade through Madrid.

Less than four months after the end of the Spanish civil war, World War II broke out, and with the early German victories it was expected that Franco would declare Spanish support for the Axis.

Even after Italy's entering the war and the defeat of France, Spain remained neutral. On October 12, 1940, Adolf Hitler traveled to the French-Spanish frontier to meet Franco. Franco left San Sebastian for the 30-minute train journey, which took three hours.

Later Franco was to use this to illustrate his reluctance, but it seems more probable that it was to do with the dilapidated state of the railway stock. The meeting went badly. Apparently, Franco wanted control of the French North African colonies as his price for involvement in the war.

Franco also opposed the Germans' establishing bases in Spain, but he did allow submarines to refuel. He also allowed Spanish volunteers to serve on the Russian front and allowed the formation of the "Blue Division," as they were known.

Franco's caution meant that he did not attack Gibraltar, which he could probably have easily captured and which the Germans wanted him to take. However, he did take control of the international city of Tangier— which was returned to international rule at the conclusion of the war.

Although Franco had remained neutral in 1945, Franco's government was treated as a pariah. In December 1946 the United Nations General Assembly condemned Spain and urged its members to withdraw their ambassadors from Madrid. It was not until 1955 that Spain was admitted to the United Nations, and it did not join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) until 1982.

Gradually, Franco changed the overt nature of his regime. Although Franco dominated the political scene, the Spanish economy was devastated, and unemployment and underemployment were widespread.

Franco was anxious to get economic aid from the United States and softened his stance in 1947 by holding a referendum on the "Law of Succession" that established Franco as a dictator acting as a regent of the Kingdom of Spain. It was, however, the first time the Spanish people had voted in 11 years.

Franco also started courting Argentina, which was the only country that had flouted the United Nations, request to withdraw ambassadors in 1946. Argentina at that time had not had an ambassador in Madrid, but after the UN vote it hastily filled the vacancy.

Soon afterward it was announced that Juan Perón, president of Argentina, and his wife, Eva, would visit Madrid. Eventually, it was Eva who made the state visit, and this signaled the end of Spain's international isolation.

In 1969 Franco finally named his successor as Prince Juan Carlos de Borbón, with the title prince of Spain. Technically, the father of Juan Carlos had a greater claim, but this also annoyed Carlists, who had supported Franco in the civil war. Four years later Franco gave up the post of head of government but remained head of state and commander in chief of the armed forces.

He died on November 20, 1975, and was buried behind the high altar at the basilica at the Valle de los Caidos (Valley of the Fallen), a church carved into a mountain that officially serves as a memorial for the dead of both sides of the civil war but has long symbolized the nationalist cause.