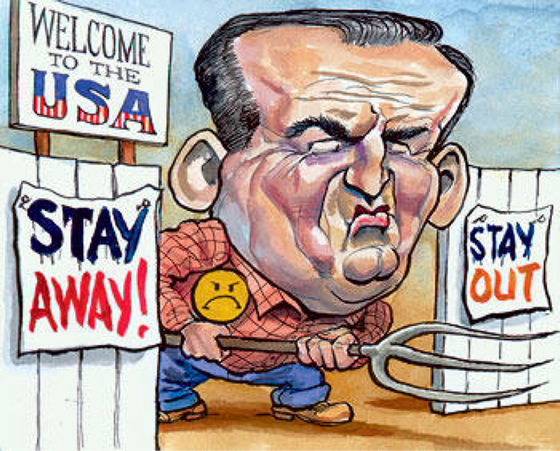

Nativism is antiforeign, anti-immigrant sentiment, and it has been common throughout U.S. history. Nativism is cyclical in U.S. history. Generally, when the United States is expanding and optimistic, then immigrants are welcome. When the country is stagnating and cynical, then it turns on immigrants. U.S. nativism is more about Americans than it is about foreigners.

Benjamin Franklin was nativist when he wondered whether the Pennsylvania Germans of his time were capable of becoming assimilated. The Federalist Party of 1798 was nativist in trying to preserve an antidemocratic property-protecting system from immigrant editors and pamphleteers.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were nativist as well as political. The anti-Catholicism of the 1830s was nativist. The run-up to the Civil War distracted from nativism, and the resurgence came after the war when anti-Asian sentiment, which originated on the West Coast in the 1850s, resulted in national legislation, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

|

Anti-Asian laws would continue to pass until the 1920s, as would anti-European laws, directed against the different and impossible-to-assimilate new immigrants of the late 19th century who were seen as a threat to an American way already under pressure from the capitalism and industrialism that destroyed the traditional agrarian United States during the Gilded Age.

Organized labor, the American Protective Association, and eugenics groups sought immigration restrictions, English literacy laws, and restrictions on parochial schools. They outlawed the teaching of foreign languages in schools. Foreign was seen as undesirable.

Red Scares

World War I stimulated the nativist desire for restriction. Anti-Germanism became antiforeignism, which became antiradicalism, which culminated in the Red Scare of 1919 and 1920 and the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anticommunist, and antiforeign on top of its historical antiblack prejudice. The Klan drew 5 million members.

Again, organized labor asked for restriction of immigrants because they worked for substandard wages and brought the wages of natives down. Another reason for restriction was that the war had produced millions of refugees who might swamp American prosperity if left unchecked.

|

| Closing the Door on Immigration |

Congress passed a temporary immigration restriction law in 1921 and followed it with the National Origins Act of 1924, which established immigration quotas based on the population profile of the United States in 1890. The law also effectively excluded all Asians.

Immigration control was not sufficient to quell the nativist urge. In the 1920s the Klan enjoyed a national presence. Although born in the South and based on racism, it took on a broader appeal. The Klan resurgence began after D. W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation recalled the 19th-century Klan as heroic.

In Georgia William Simmons, a former Methodist minister, reawoke the Klan. It was powerful in Indiana, Oklahoma, and Oregon, and it had a presence in other western states such as Utah. The Klan of the 1920s was opposed to the new morality, the lack of enforcement of Prohibition, and the increase in crime.

|

It was a backlash by a segment of the United States that was losing the battle to modernity. Those who were bypassed by the changing economy, the shift to the cities, and the new ideas of modern art, psychology, and modernism lacked the means to change what was happening to them.

Anti-Semitism was strong in the first half of the 20th century, before and after the Klan. Its practitioners included Henry Ford, whose Dearborn Independent had a readership of about 700,000.

The Independent featured articles on Jewish gamblers, mobsters, and the dissipation of Jewish music. The Klan literature featured comparable complaints about Jewish jazz and short skirts. Most of all, the anti-Semites blamed Jews for communism.

They accepted that the Protocols of the Elders of Zion announced a worldwide Jewish conspiracy, and they believed that international Jewry, wealthy and powerful, had bought the Bolsheviks and influenced allied armies to leave Russia during the civil war, thus allowing the Bolsheviks to prevail.

Anti-Semitic nativism also arose in the Military Intelligence Division, which carefully tracked Jews in the military for Bolshevik, then communist, tendencies, an activity that did not wane until the 1950s and 1960s. Nativist anti-Semites feared that the Jews were conspiring against their Christian nation.

Also active in the 1920s were the race theorists Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard, who feared the denordicizing of the people of the United States due to the mingling of what they regarded as superior northern Europeans with the "lesser races."

White supremacist groups emerged in the 1930s and 1940s, emulating Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. Silver Shirts, Khaki Shirts, and Brown Shirts marched and made a display but failed to attract a large following. The mood of the United States in the 1920s and 1930s was isolationist.

Rather than "over there," the slogans were "America First" and "Fortress America." Immigration exclusion fit the mood, even when the persecution of Jews turned fatal. The United States failed to lift immigration restrictions to help those it did not want on its shores.

Nativism became quiet after the Exclusion Law of 1924 because immigration slowed during the Great Depression and World War II. Even without factoring in the deportation of half a million Mexican migrant workers and their families (many of them U.S. citizens) in the 1930s, immigration was negative.

More left than came in. World War II opened the door slightly, too much for holdover nativists from the 1930s such as Gerald L. K. Smith, who moved from Huey Long's Share the Wealth, through America First, to radical right Christian anticommunism in the 1950s.

Even the immigration reform of the 1950s maintained restrictions, allowing time for the southern and eastern European immigrants to assimilate and providing only token access for Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and other Asians.

The major change came with the Immigration Reform Act of 1965, which sought to renew immigration by the old European immigrants. The act almost absentmindedly brought the third world to the United States.

Demographic, linguistic, and cultural diversity generated a new feeling by some U.S.born citizens that the country was getting away from them. The economy was in crisis due to the 1970s energy crisis and the Vietnam War, which brought about "stagflation" as well as massive increases in the foreign population.

The newcomers—Vietnamese, Cubans, and South Americans—were scapegoated. The problem was bilingualism, and in the early 1980s the nativists began agitating for English-only in government and sometimes in the private sector.

Some U.S. citizens thought that English-only was a tool for forcing assimilation on immigrants (for their own good), but others used English-only as an excuse to terminate bilingual access to essential services.