|

| Lytton Commission |

On the night of September 18, 1931, the Japanese Kwantung Army stationed in Manchuria, China's northeastern provinces, staged a minor bomb explosion on the tracks of the South Manchurian Railway outside Mukden, the administrative capital of Manchuria.

Claiming that it was Chinese sabotage, the Japanese military swung into action, simultaneously attacking over a dozen Chinese cities in the region. Japanese units from its colony Korea invaded to broaden the attack. This was known as the Manchurian incident, or Mukden incident.

The Chinese army was no match for superior Japanese forces. Therefore, China decided not to resist militarily and appealed to the League of Nations for support. It also appealed to the United States as signatory of the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 and the Washington Treaty of 1922. International support for China was expectedly lukewarm.

|

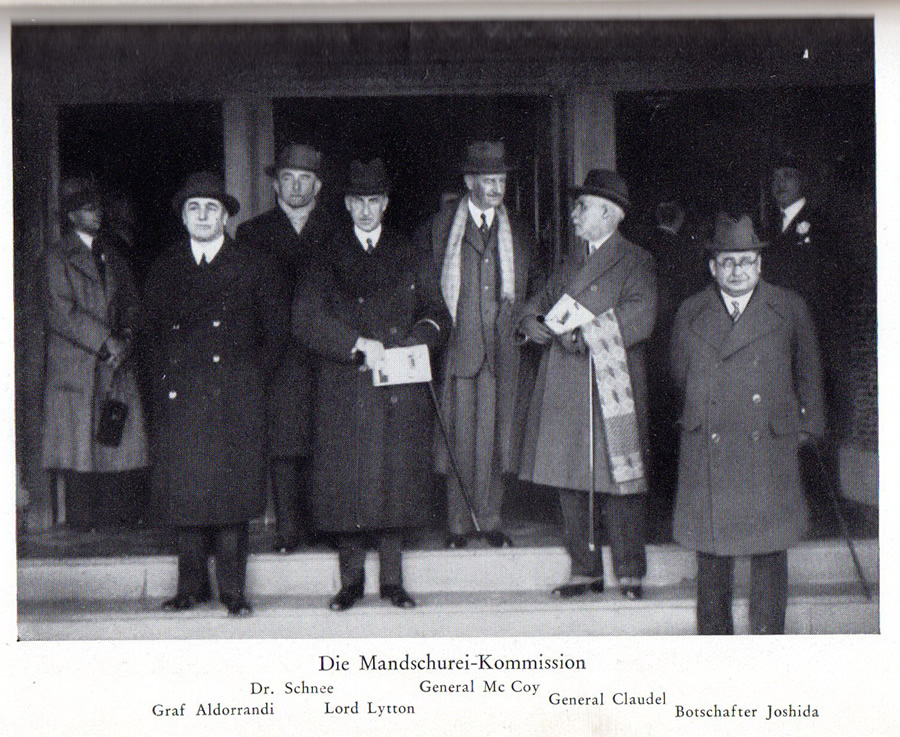

However, the league assembly passed two resolutions, on September 30 and October 24, enjoining Japan to withdraw its forces, which the Japanese government promised to honor, but they had no effect on its military. On December 10 the league decided to dispatch a commission of investigation under British diplomat Lord Lytton, which spent six weeks in Manchuria plus some time in Japan and China.

Japan conquered Manchuria in five months, then established a puppet state called Manchukuo (state of the Manchus) on March 9, 1932. Next Colonel Doihara Kenji, intelligence chief of the Kwantung Army, enticed the last Qing (Ch'ing) emperor, Pu-i (P'u-yi), to Manchuria, installing him as chief executive (later as "emperor") in a regime totally controlled by the Japanese.

The Lytton Report, submitted to the league on October 1, 1932, refuted Japan's claim that Manchukuo had local support, condemned Japan for aggression, and recommended the restoration of Manchuria to Chinese sovereignty.

It also recommended the maintenance of the Open Door policy in Manchuria and special consideration for Japanese and Soviet commercial interests in the region. China signaled total acceptance of the report's recommendations, as did the league assembly on February 14, 1933, with one dissenting vote—Japan's. On March 27 Japan announced its resignation from the league.

The failure of the League of Nations to halt Japanese aggression against China in the Manchurian incident signaled its impotence and doomed the international organization. The United States had on January 7, 1932, announced its Non-Recognition Doctrine (or Stimson Doctrine after Secretary of State Henry Stimson), stating that it would not recognize any situation created as a result of war in violation of the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Japanese militarists, encouraged by their success, would ignore both the league and the United States to pursue aggression.