Founded on idealism and championed by U.S. president Woodrow Wilson as part of his Fourteen Points plan for international peace, the League of Nations foundered on the geopolitical realities of the interwar period. Designed to prevent war as a means of resolving disputes between countries, the league proved unable to halt the Italian conquest of Ethiopia, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, or Nazi Germany's rearmament.

Yet even given its failures the League of Nations inspired leaders to rethink traditional diplomatic practices and embodied the pacific, cooperative ideals that another generation would try to realize through the United Nations.

Prior to the league's creation, international relations had been the province of ambassadors exchanged between governments who then lived in the country to which they had been posted. Although these diplomatic procedures did not disappear, the league sought to build on another, more recent development in diplomacy: the international conference.

|

Institutions such as the International Court of Arbitration at The Hague had lacked the power to halt the slide into World War I. Nevertheless, international conferences of the later 19th and early 20th centuries had established rules for war, standard time, and policies on matters of common interest. The league's creators drew upon such precedents, though the great powers themselves did not abandon the more traditional modes of secret diplomacy.

The idea for the league came originally from Woodrow Wilson, who wished to create a real and lasting peace. The creation of the league was an integral part of his Fourteen Points and was the only point to be approved by the Allies.

At home, a group of senators and representatives headed by Henry Cabot Lodge opposed U.S. membership in the league and effectively prevented the country from joining. In Wilson's vision, the League of Nations would act as a force to prevent the outbreak of war and create stability on the global stage.

|

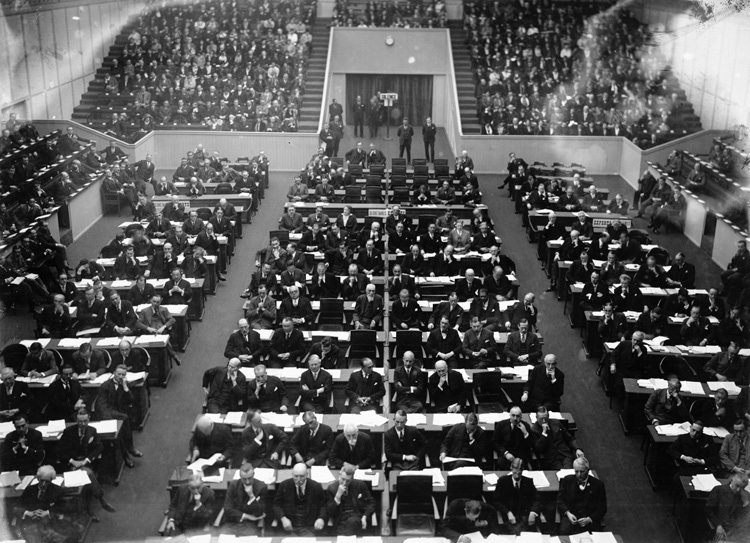

| A meeting of League of Nations |

The covenant upon which negotiators agreed in 1919 included article 10, in which league members undertook collectively to defend "the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members."

Actual practice departed from this principle, in part because article 5 required binding resolutions to receive unanimous consent and in part because the league had no army in its service nor any other means to impose its will on an aggressor.

When the U.S. Senate rejected the treaty and refused membership in the League of Nations, the institution experienced a significant setback in its efforts to acquire legitimacy and real power to pursue its peaceful agenda.

The League of Nations was composed of a secretariat, a council, and an assembly. Sir Eric Drummond, formerly of the British Foreign Office, served as secretary-general for the first 14 years (1919–33) and helped to attract 675 men and women to work as an international civil service. The council met at least annually.

At its foundation the body included France, Britain, and Italy as permanent members, along with other smaller powers. The council grew to 10 in 1922 and to 14 in 1926, when the additional members were supposed to counterbalance Germany's admission to the council. The membership of the assembly was largely European and South American, as most African and many Asian countries remained under European rule until after World War II.

Although best known for its failures in the area of collective security, the league began its existence with several successes. The league council prevented war between Sweden and Finland over the Aaland Islands (1920), between Germany and Poland over Upper Silesia (1921), and between Greece and Bulgaria over the exact location of their shared border (1925).

This raised some questions about whether the league would be able to deal with disputes that touched the interests of a country such as Britain or France. In fact, the great powers continued to pursue old-fashioned diplomacy and treaties, such as the Locarno agreements.

Britain would not accept measures to reinforce the league's powers to react against aggression. The league sponsored Disarmament Conference met during the late 1920s and early 1930s until Hitler withdrew Germany from the conference and from the league in 1933.

The weaknesses of the league became especially apparent in 1931. During its meeting in Geneva, the assembly learned that Japan had begun to attack the Chinese in Manchuria. As the days passed news grew worse, and the Chinese representative called upon the league council to authorize a response.

After vacillating and accepting disingenuous assurances from the Japanese representative about his country's intentions, the league sent a commission of inquiry under Lord Lytton that arrived in April 1932. The Japanese army already exercised effective control over much of "Manchukuo."

The Lytton Commission submitted a 100,000-word report on September 4, 1932. The assembly accepted its conclusion that the Japanese had violated the league covenant. It condemned the aggression against China but did nothing further. Japan simply withdrew from the league in March 1933.

Similar instances of impotence occurred after Italy invaded league member Ethiopia in 1935. Pierre Laval, the French foreign minister, and Sir Samuel Hoare, his British counterpart, went outside of the league framework to seek ways to appease Benito Mussolini, to serve their own interests, and to avoid war.

These secret negotiations later became public knowledge, much to the chagrin of the participants, but the unwillingness of Britain and France to support the league did not change. The league first attempted conciliation and then studied the crisis.

The assembly agreed that blame fell upon Italy, yet it could do nothing more than impose economic sanctions. The completion of Italian conquest indicated the failure of the sanctions, so the British pressed for them to be lifted in 1935. League members quietly accepted Italy's annexation of Ethiopia.

The League of Nations continued to meet in the late 1930s. It dissolved in 1946, when the United Nations came into existence. Founders of the United Nations attempted to learn from the supposed shortcomings of the league, especially with regard to collective security and the composition of the council.