|

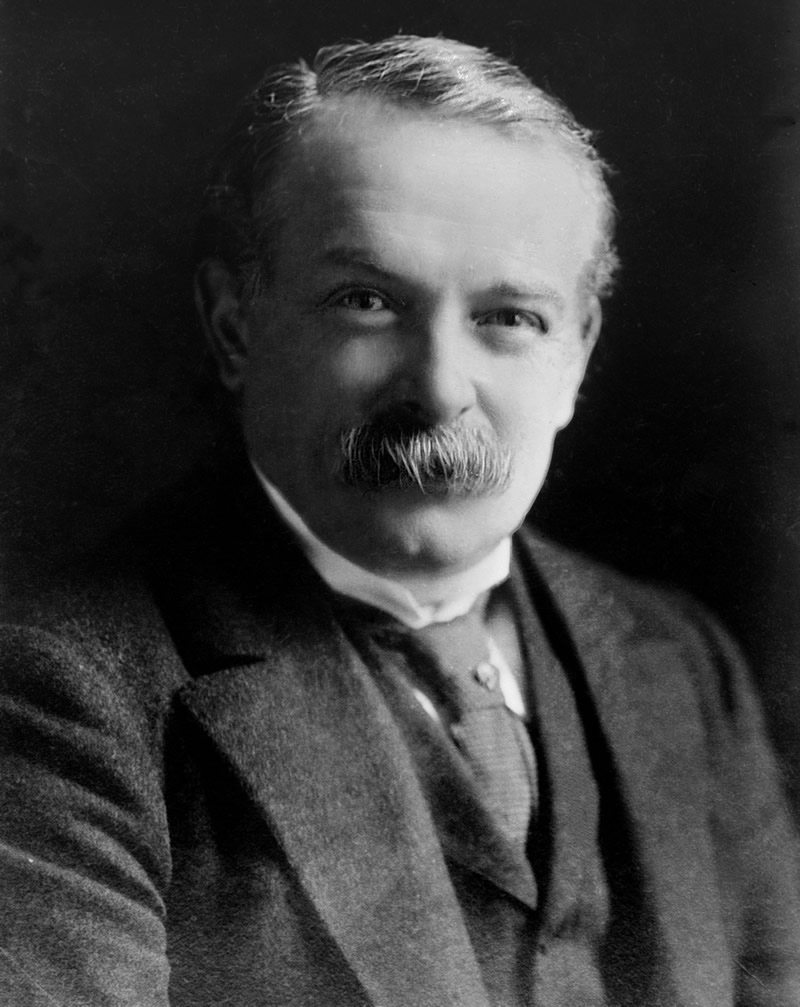

| David Lloyd George |

David Lloyd George was the most dominant figure in British politics in the first quarter of the 20th century. Although Welsh on both sides of his family, he was actually born in Manchester, England, in 1863. His father, William George, then a headmaster of an elementary school in Manchester, died 17 months later, leaving his pregnant widow to raise the children.

His mother, Elizabeth, took her family back to her home village of Llanystumdwy in north Wales to live with her bachelor brother, Richard Lloyd, a shoemaker and copastor of a little Baptist chapel. A Welsh nationalist and deeply religious, Richard Lloyd played an active role in the upbringing of young David, imbuing him with many of his formative beliefs.

At the age of 14, David was apprenticed to one of the leading firms of solicitors in Portsmouth, passing his final examinations in 1884. During the early years of his practice, he met and married Margaret Owen, who bore him two sons and three daughters.

|

Bitten by the political bug while in his late teens, Lloyd George associated himself with the Liberal Party. In 1890 he was elected to Parliament for the Caernarfon Boroughs, a seat that he would retain for the next 55 years.

A gifted speaker, audacious, and industrious, he soon became a leading spokesman for the radical wing of the party. As a pacifist he inveighed against the immorality of the Boer War in South Africa and expressed sympathy for the Boer farmers.

When the Liberals returned to power in 1905, Lloyd George was appointed president of the Board of Trade, a position he held for three years, during which he sponsored much important legislation. He took over as chancellor of the Exchequer at a time when the government needed to find new sources of revenue to pay for the cost of social programs and additional battleships to keep ahead of the ambitious German naval program.

Accordingly, his "peoples budget" in 1909 called for a heavy tax on unearned income such as inheritance, increased value of land, and investments. The House of Lords, which was dominated by Conservatives, vetoed the budget, defying the House of Commons' traditional control of taxation. This provoked a constitutional crisis, forced two general elections, and ended in 1911 with the passage of the Parliament Act, which severely curtailed the powers of the House of Lords.

When the question of Britain's entry into the war was debated in the cabinet in the opening days of August 1914, Lloyd George sat on the fence until Germany's invasion of neutral Belgium provided him with a facesaving formula to join the ranks of the interventionists. Just as he had preached pacifism prior to 1914, he pursued his new course with vigor and determination.

At the Exchequer he handled the financial problems posed by the war, and when a coalition government was established in May 1915, Asquith appointed Lloyd George to head the new Ministry of Munitions. Here he applied the same energy to stimulate the production of munitions as well as push for the manufacture of bigger and more efficient guns.

In the summer of 1916, he became secretary for war, succeeding Horatio Herbert Kitchener, who drowned when the ship on which he was traveling to Russia struck a mine and sank. As the year wore on, Lloyd George grew increasingly disenchanted with Asquith's lack of drive, and on December 1, with the backing of the Conservatives, he proposed that a small committee should be created to run the war with himself in charge.

The king asked Bonar Law, the Conservative leader, to form a government, but he declined. Lloyd George was left as the logical alternative, and, when invited to serve as prime minister, he willingly accepted the challenge.

He formed a coalition made up Conservatives and Liberals. His intrigue against Asquith split the Liberal Party between a faction loyal to him and another loyal to the former prime minister. The breach became permanent and finished the Liberal Party as a major political force.

Lloyd George made institutional changes at the outset, creating new ministries and substituting a small war cabinet, whose members were free from departmental responsibilities, for the unwieldy body that had hitherto conducted affairs.

The prime minister's central concern was to change the direction of the war. Instead of concentrating on the western front, Lloyd George favored attacking Germany's allies, where progress was expected to be easier and the cost substantially less.

As an amateur strategist, he never understood that the war could only be won by defeating the German army. Even if Douglas Haig had employed more imaginative tactics early on, the price of victory would have been tragically high.

In the winter of 1917–18, Lloyd George tried his best to thwart Commander in Chief Haig's plans for an offensive by denying him the troops that he had requested. It was a misguided action that almost spelled defeat for the Allies when the Germans attacked the British sector in force in the spring of 1918.

The crisis led to the establishment of a unified Allied command under General Foch, in which military effectiveness was improved, and by May the situation had stabilized. Haig's series of victories in the summer and fall were instrumental in inducing the German government to ask for an armistice, but it was Lloyd George who represented himself as "the man who won the war."

In truth, his legacy does not rest on his management of the war, where he did more harm than good. It was on the home front that he left his mark: safeguarding shipping and maintaining food supply, increasing war production, mobilizing manpower, and providing an unflagging display of optimism and resolve when things looked bleak.

His popularity at an all-time high, Lloyd George, popularly known as the "fighting Welshman," won an easy electoral victory in December 1918, which allowed him to continue the coalition. He played a leading part at the Paris Peace Conference, steering a middle course between Woodrow Wilson's idealism and Georges Clemenceau's demands. It is to his credit that the final terms were not as severe on Germany as they would have been.

His failure to rebuild the economy; a personal scandal in which he traded peerages and other honors for campaign contributions; the granting of independence to Ireland, which cost him Conservative support; and a reckless foreign policy that almost led to an unnecessary war with Turkey spelled his downfall in October 1922. He never regained power and died in March 1945 at the age of 82.