|

| Bulgarians overrun a Turkish position at First Balkan Wars |

During 1912–13 the Balkan Peninsula witnessed two wars: the First Balkan War, which saw an alliance of Balkan states all but destroy the Ottoman presence in the region, and the Second Balkan War, fought between the former allies over the division of the spoils. The Balkan Wars were the result of the incomplete processes of nation-state formation in southeastern Europe at the beginning of the 20th century.

Ever since the

Congress of Berlin in 1878 warranted the continued existence of the

Ottoman Empire in the region, the dominant foreign policy goal of the Balkan states had been expanding into European provinces. Their main motive was to recover territories that were perceived to be under foreign occupation.

Thus, one of the dominant claims of the Balkan states at the time was that their fellow ethnic kin were still oppressed by the Ottoman sultan. Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro justified their desire to extend into Ottoman-controlled Macedonia and Thrace through the principle of "liberation" of subjugated populations.

For this purpose each country supported armed groups of its conationals that subverted and challenged the Ottoman regime. One of the aims of the

Young Turk revolutions of 1908 had been precisely to end these revolts, suppress rival national identities, and "Ottomanize" the population.

In this context the situation in the European provinces of the Ottoman Empire impressed on the Balkan governments the need to cooperate. External great powers such as Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Italy were also sizing up the

opportunity to get their share of the crumbling Ottoman state, which was referred to at the time as the "sick man of Europe."

The war that Italy launched against the Ottoman Empire in September 1911 hastened the resolve of Balkan governments to sit at the negotiating table. On March 13, 1912, Bulgaria and Serbia signed a treaty of alliance and friendship, which was accompanied by a secret annex anticipating war with Turkey and providing for the division of territorial acquisitions in case of a successful war.

|

| Ottoman forces in the Balkans |

According to this annex the territory of Macedonia was to be divided into three zones: two zones that would belong, respectively, to Bulgaria and Serbia and a third one that was contested and would be subject to the arbitration of the Russian czar. At the same time Greece and Bulgaria were conducting separate negotiations, which culminated in the signing of a mutual defense treaty on May, 29, 1912, assuring support in case of war with Turkey.

Bulgaria and Serbia had separate discussions with Montenegro, which concluded with verbal agreements that provided for mutual actions against the Ottoman state. By autumn the Balkan governments had managed to prevail over their mutual distrust and had formed a Balkan League premised on an extensive system of bilateral treaties.

The Balkan Wars began immediately afterward. On September 26, 1912, Montenegro opened hostilities invoking a long-standing frontier dispute as an excuse for declaring war. On October 2 Turkey hastily concluded a peace treaty with Italy, and on the next day it broke diplomatic relations with Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro but tried to mend relations with Greece.

|

| Serbian army uniform |

On October 4, 1912, the Ottoman Empire declared war on the Balkan League. In turn Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro declared war, accusing the Sublime Porte of not having implemented an article of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, which insisted on the recognition of the minority rights of their conationals in Macedonia. This event began the First Balkan War.

With specific manifestos the governments of Athens, Belgrade, and Sofia informed their citizens that they were to fight for a common cause and against Ottoman tyranny. Military operations began on all frontiers of European Turkey.

Within a month after the start of hostilities, the Balkan armies had won spectacular victories on all fronts. The Bulgarian troops had pushed the Ottoman army to the Çatalca line of defense, just 40 kilometers outside of Istanbul, and had besieged Adrianople (modern-day Edirne in Turkey).

The Serbs had surged into Macedonia, reaching Monastir (Bitolj) on November 17, 1912, and together with Montenegrin forces had occupied the Sandzak of Novi Pazar and had besieged the town of Scutari (today Shkodra in Albania).

The Greek troops advanced in Thessaly. They entered Thessalonica on October 28, only a few hours before the arrival of a Bulgarian detachment, and the town was occupied by both armies. In Epirus Greek detachments advanced all the way to Janina (present-day Ioannina in Greece) and on November 10 laid siege to the city.

By December 1912 the Ottoman rule in the Balkans was over. Save for the besieged Adrianople, Scutari, and Janina, the Ottoman troops had been driven out of the former European provinces beyond the Çatalca line covering Istanbul.

|

| Depiction of the Battle of Sarantaporos during the First Balkan War |

Alarmed by the success of the Balkan armies, the great powers imposed an armistice on the belligerents on December 3, 1912. It was signed by Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro, who pledged that their troops would remain in their positions.

Greece, however, did not join in, as it wanted to continue the siege of Janina and carry on with the blockade of the Aegean coastline. Yet despite the continuation of hostilities in Epirus, Greece, together with Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Turkey, took part in the peace conference that opened in London on December 16, 1912.

After two months of negotiations, toward the end of January 1913, a peace agreement seemed to be in sight. However, on January 23, 1913, a group of disgruntled Turkish officers overthrew the Ottoman government.

|

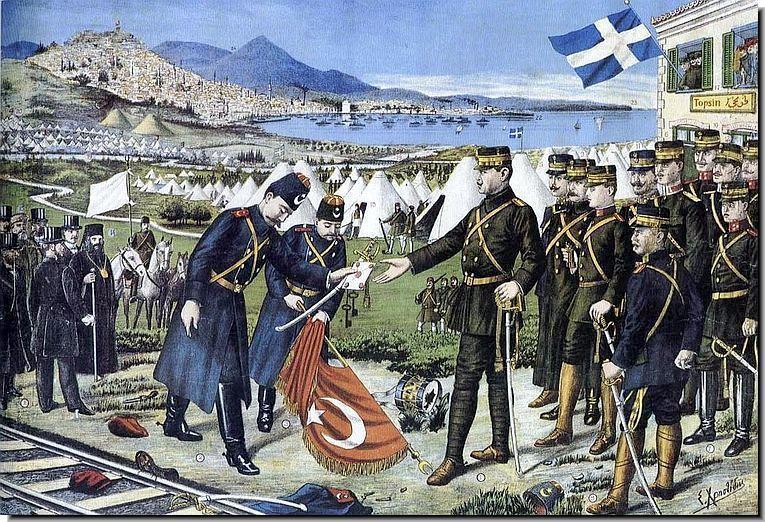

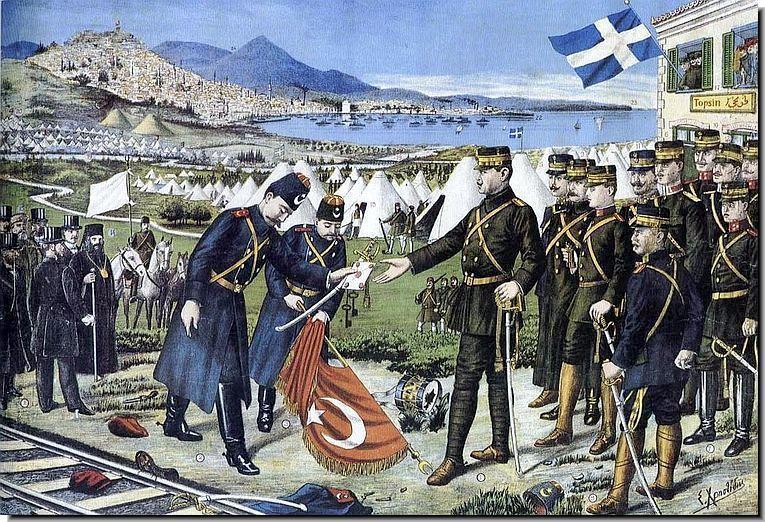

| greece defeats turkish |

By January 30 fighting had resumed on the Çatalca line. On February 21 the Greek army captured Janina, and on March 13 the Bulgarian troops broke the Turkish defenses at Adrianople and occupied the city. On April 10, 1913, Montenegrin and Serb forces entered Scutari, but they had to withdraw eventually under the threat of war from Austria-Hungary.

At this juncture the great powers again insisted on armistice and proposed a peace treaty, which projected that all the territory west of a straight line stretching between Enos (Enez) on the Aegean Sea and Midia (Midye) on the Black Sea would be ceded to the Balkan states, that this territory was to be divided between the Balkan states under the supervision of the great powers, that an Albanian state would be established, and that the future of the Aegean islands was to be decided by international arbitration. By the end of May 1913 all parties taking part in the First Balkan War were compelled to agree to these conditions at the Treaty of London.

Yet at that time rifts started to appear among the Balkan allies over control of the "liberated" territories, with skirmishes between the Greek and Bulgarian troops occupying Thessalonica. Furthermore, the creation of an Albanian state confused the agreements made between Athens, Belgrade, and Sofia before the start of hostilities.

Greece and Serbia insisted that the emergence of Albania deprived them of their anticipated gains on the Adriatic. Therefore, they asserted their right to retain the territories that their armies had already occupied in Macedonia at the expense of Bulgaria.

|

Serbian troops examining rifles, captured in large quantities from the Turks,

at Skopje, October 1912 |

Sofia insisted that the acquired territory should be divided in accordance with the principle of proportionality of the acquisitions to the military input. Athens and Belgrade insisted on a principle ensuring the balance of power among the members of the Balkan League.

Because of their shared interests, Greece and Serbia entered into secret negotiations and on May 19, 1913, reached an agreement for a military pact against Bulgaria. At the same time Romania, which had so far remained neutral, took the opportunity to obtain some concessions for itself.

On the pretext of concern about the treatment of the Vlach population in Macedonia, Romania demanded that Bulgaria give up some of its territory in the contested Dobrudja region.

Under pressure from Russia, Bulgaria agreed to cede the town of Silistra and the surrounding area to Romania. At the same time Bulgaria, urged by Austria-Hungary, refused to concede any territory in Macedonia to either Serbia or Greece.

In the beginning of June there were several military clashes between Bulgarian and Serbian troops. However, it was on June 16, 1913, by an oral command from the Bulgarian czar Ferdinand, that Bulgarian troops launched a full-scale attack on Greek and Serbian forces.

Ferdinand was partly encouraged by promises by Austria-Hungary of assistance. However, a recent visit to Bulgarian-occupied Adrianople had also stirred in him a desire to revive the medieval Bulgarian Empire and capture Constantinople. Thus, on June 16, 1913, the Second Balkan War began.

In the first few weeks the Bulgarian army had some limited success in holding to its positions, but by the end of the month the Serb, Montenegrin, and Greek armies were already on the offensive. On June 28, 1913, Romania also joined in the fray and declared war on Bulgaria.

By July 6 Romanian troops had occupied the whole of northern Bulgaria, and a Romanian cavalry detachment arrived at the Bulgarian capital of Sofia. On June 30, 1913, Ottoman troops began attacks on Bulgarian positions, and on July 10 they recaptured

Adrianople. By mid-July Bulgaria was suffering defeats on all fronts and had lost most of the territory it had gained during the First Balkan War.

|

| Serbian Soldiers - Second Balkan War 1913 |

The Second Balkan War ended in late August 1913. After a personal intercession by

Emperor Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary, a peace conference was convened at Bucharest from July 17 to August 16, 1913. As a result of the Bucharest Peace Treaty, Serbia kept the territories of Macedonia, which its troops had obtained during 1912. Thus, it added Kosovo, Novi Pazar, and Vardar Macedonia to its territory.

Greece secured over half of Macedonia (Aegean Macedonia), the southern part of Epirus, and an extension into southern Thrace. Bulgaria received the smallest part of Macedonia (Pirin Macedonia) and a section of the Aegean coast, but it had to cede southern Dobrudja to Romania.

As a result of its treaty with the Ottoman government, Bulgaria also gave up its claims to Adrianople. In the meantime an independent Albanian state was officially created by the Conference of Ambassadors in London on July 29, 1913.

|

| Second Balkan War |

This series of treaties concluded the Second Balkan War. It was bloodier than the first one, cost more lives, witnessed horrific crimes against civilians, and deepened the divisions between the Balkan states. All sides in the Balkan Wars acted in a way that indicated that their main aim was not simply the acquisition of more territory but also ensuring that this territory was free of rival ethnic groups.

The atrocities committed during the Balkan Wars led to the establishment of an international commission of inquiry set up by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It produced an extensive report detailing the crimes committed by all combatants against their enemies and against civilian populations.

Instead of resolving the problems between nationalities in the region, the Balkan Wars further exacerbated interethnic tensions. The psychological trauma of the wars and the displacement of populations increased the suspicions and divisions between the Balkan states.

The new boundaries that were established as a result of the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913 produced conditions for persistent resentment and created a feeling of unjust expropriation of territory and eradication of people.

The suffering and the perceived injustice that all nations in the Balkans experienced molded the foreign policies of regional states. In this respect the Balkan Wars became a major source of the grievances that contributed to the beginning of

World War I.