|

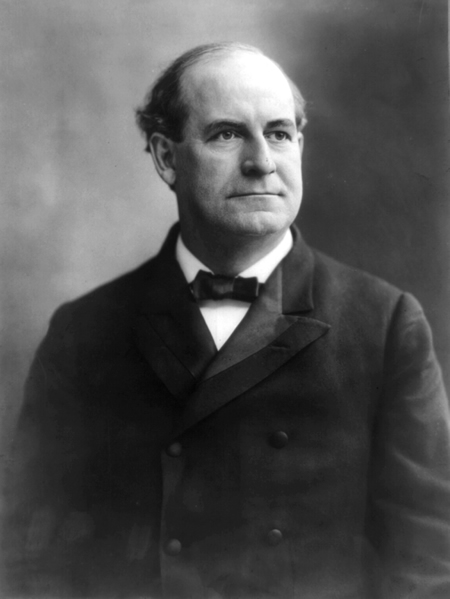

| William Jennings Bryan |

Although he lost the presidency three times, William Jennings Bryan used powerful oratory and sympathy for America's downtrodden to transform the Democratic Party. In the Woodrow Wilson administration, Bryan tried unsuccessfully to keep the United States out of World War I.

A committed Christian, he spent his final days in Tennessee, opposing Darwinian evolution at the Scopes trial and thereby entering history as a hero to the devout and a laughingstock to an urbanizing nation.

Bryan grew up in rural Salem, Illinois, becoming a lawyer and a Democrat like his father. In 1887, seeing greater political opportunity, he moved to Nebraska, where he became in 1890 only the second Democrat to win a congressional seat in Nebraska's 23 years of statehood.

|

In an era that esteemed oratory, Bryan spoke clearest and loudest, attracting national attention as he took up "prairie insurgency" causes that challenged both major parties. A supporter of direct senatorial election and banking reform, he called for federal intervention on behalf of farmers and laborers who felt themselves oppressed.

Bryan sided with those who demanded unlimited coinage of cheaper silver money, positioning himself in the depression year of 1896 as the one candidate who could make populist demands a reality. The Chicago nominating convention erupted in cheers when Bryan finished his 20-minute "Cross of Gold" speech. The next day Bryan outpolled 12 other hopefuls, winning nomination on the fifth ballot.

Bryan broke campaign tradition by barnstorming 18,000 miles through 26 states, while Republican senator William McKinley conducted a genteel campaign from his Ohio front porch. Despite attracting a huge following of "believers," Bryan could not match the Republicans' fund-raising prowess and had trouble attracting urban support. He lost decisively and would lose again to McKinley in 1900 and to William Howard Taft in 1908.

|

| William Jennings Bryan campaign poster |

Although he volunteered for the 1898 Spanish American War (but never saw action), Bryan opposed imperialism and especially opposed U.S. efforts to rule the Philippines. Yet he disregarded Jim Crow laws that stifled African-American political participation. Bryan calculated that his political success depended on white votes from the "Solid South." Even so, black leader W. E. B. Dubois saw hope in the "Great Commoner's" concern for the poor and exploited.

Bryan's tenure as Woodrow Wilson's secretary of state was disastrous. Wilson, who meddled in the Mexican Revolution and the Caribbean, did not share Bryan's idealistic pacifism. In June 1914 World War I broke out in Europe. Bryan counseled true neutrality but resigned after a German U-boat attack on Britain's Lusitania in 1915 killed 128 Americans and prompted a harsh presidential warning.

Although Bryan was a dedicated Christian and teetotaler who championed Prohibition, he was no rube. He became wealthy from speaking engagements yet supported the graduated income tax. He traveled widely abroad, visiting Russian writer and pacifist Leo Tolstoy.

Bryan (and his wife, Mary Baird Bryan) strongly backed women's suffrage. By the 1920s, though, Bryan seemed quaint to a new generation. His focus on Darwinism's evils and the Bible's truth seemed especially antimodern, even though he was among the first evangelists to speak on radio.

So when Bryan was brutally interrogated during the 1925 Scopes trial by famed lawyer Clarence Darrow, once a Bryan supporter, the legendary orator's weak showing seemed to prove the idiocy of his cause. Six days later Bryan, a diabetic, died in his sleep in Dayton. Mourned by thousands along its route, Bryan's funeral train carried him to burial in Arlington Cemetery. The Democratic Party of Franklin D. Roosevelt and other future leaders would owe much to Bryan's initiatives.