|

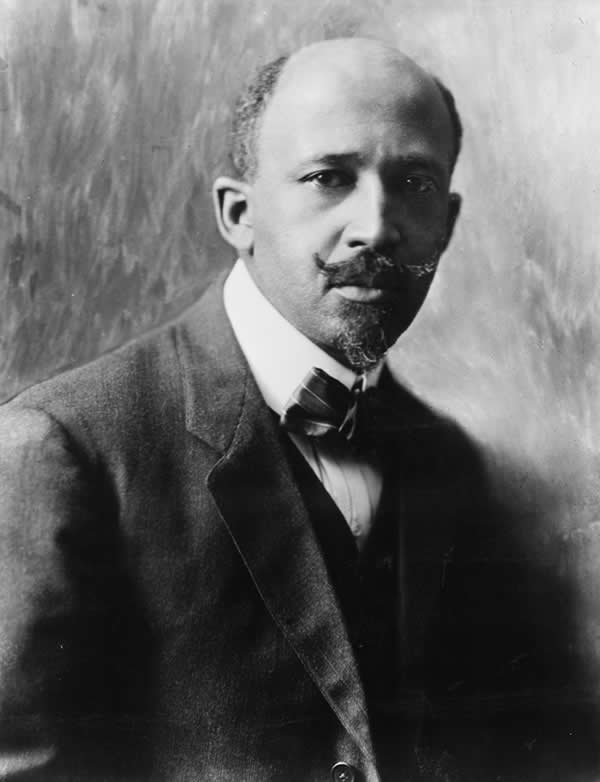

| William Edward Burghardt DuBois |

In a life spanning nearly a century William Edward Burghardt DuBois was one of the most brilliant, contentious, and significant leaders in the post-slavery United States.

A sociologist and the founder of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), DuBois wrote extensively on issues of race—the "problem of the color line"—and worked to achieve equality for African Americans weighed down by poverty and prejudice. Disillusioned with U.S. racial politics, DuBois late in life became a communist and left the United States for Africa, where he died a citizen of Ghana at age 95.

DuBois was born in Massachusetts just after the Civil War. As part of a tiny black minority, he suffered occasional racism, but not until he attended Fisk College in Nashville, Tennessee, did he see firsthand how emancipated slaves and other people of color were treated in the former Confederacy. By 1895 DuBois had become Harvard University's first black Ph.D.

|

DuBois's most influential book was published in 1903. The Souls of Black Folk is a meditation on history and race that lyrically describes what both whites and blacks need to do to overcome the "two-ness" that keeps African Americans from equal participation in U.S. society.

More controversially, the book launched a stinging attack on Booker T. Washington, a former slave who as head of Alabama's Tuskegee Institute encouraged blacks to (temporarily) accept inferior status. Soon DuBois's critique of the nation's best-known black leader turned him from academic to activist.

In 1905 DuBois and 28 other opponents of Washington's accommodationist policies met secretly in Buffalo, New York, once a stop on the underground railroad, to assert new roles for African Americans. Their public meeting in Fort Erie, Canada, soon followed.

A year later members of this Niagara Movement met at Harper's Ferry, the site of John Brown's 1859 raid. Although the "Niagarites" failed to attract a large membership, they signaled a new militancy. In 1909 DuBois's group joined with liberal whites who were shocked by rising racial violence to form the NAACP.

For 25 years DuBois served the NAACP as editor of The Crisis, using the magazine to focus attention on racism and African-American demands. His scorching editorials often offended other black leaders and white supporters, but circulation and membership soared.

Unlike many others, DuBois encouraged blacks to fight in World War I, later acknowledging that soldiers' sacrifices had not translated into white respect or greater equality. During the 1920s DuBois helped to publicize the Harlem Renaissance but feuded with Jamaican Marcus Garvey, whose populist Universal Negro Improvement Association had very different goals and methods for racial uplift.

By the 1930s DuBois, who had once encouraged racial integration, was developing a separatist ideology similar to what in the 1960s would become the Black Power Movement. Leaving the NAACP in 1933, he returned to academia.

From Atlanta he questioned the desirability of school integration and espoused Pan-Africanism for black people around the world. He also saw in the Russian Revolution an ideology that might overcome racism, although he did not officially become a communist until age 95.

A foe of imperialism and nuclear weapons, DuBois was deemed a subversive by the U.S. Justice Department during the cold war. Although acquitted, DuBois soon after expatriated himself to Ghana. He died there a day before Martin Luther King, Jr., led the Civil Rights March on Washington.