|

| El Salvador / La Matanza |

La Matanza, a Spanish phrase translated as "the massacre" or "the slaughter," refers to the aftermath of an indigenous, communist-inspired uprising in El Salvador in 1932. Although precise figures of the dead are difficult to discern, it is estimated that between 8,000 and 30,000 Salvadoran Indians were killed in the state-sponsored violence.

The roots of the insurrection lay in the appropriation of communal lands for coffee production by the elites and the resulting dislocation of a large number of peasants, many of them indigenous. In the 1880s the Salvadoran government passed laws outlawing Indian communal landholdings and passed vagrancy laws that forced the landless peasants to work on the large coffee plantations owned by the elites. In response peasants in El Salvador launched four unsuccessful uprisings in the late 19th century.

Coffee production expanded into the 20th century, as the country was ruled by a coalition of the coffee-growing oligarchy, foreign investors, military officers, and church officials. In the 1920s land used to grow coffee had expanded by more than 50 percent, causing the Salvadoran economy to be heavily dependent on the international price of coffee. This expansion also created a number of peasants with vivid memories of their recent displacement.

|

The Great Depression in 1929 resulted in a dramatic decline in coffee prices. By 1930 prices were at half of their peak levels, and by 1932 they were at onethird of the peak levels of the mid-1920s. In response the coffee producers cut the already low wages of their laborers up to 50 percent in some places, in addition to cutting employment.

Meanwhile, the country was experiencing a period of democratic reform unusual in Salvadoran history. In 1930 President Pío Romero Bosque announced that the 1931 election would be a free and open election. This democratic opening allowed Arturo Araujo to win the presidency with the support of students, peasants, and workers.

Araujo was distrusted by much of the elite, whose distrust grew with his attempted implementation of a modest reform program. Araujo's presidency would be marked by increasing social and political unrest and a deepening economic crisis, accompanied by the growth of leftist unions and political groups. On May Day 1930, 80,000 farm workers marched, demanding better conditions and the right to organize.

On December 2, 1931, Araujo was deposed in a military coup, and his vice president, General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, assumed the presidency. Martínez quickly ended Araujo's program of social reform and also ended the democratic opening.

In early 1932 Salvadoran Communist Party (PCS) members led by Augustín Farabundo Martí planned a revolt against the landowning elite. The insurrection was to be accompanied by a revolt in the military. Before the revolt could begin Martí was captured, and the rebels in the army were disarmed and arrested. Martí would be executed in the aftermath of the failed revolt.

Despite these setbacks Indian peasants heeded the call of the PCS and revolted in western El Salvador. On the night of January 22 farmers and agricultural workers armed with machetes and hoes launched attacks against various targets in western El Salvador, occupying Juayúa, Izalco, and Nahuizalco in Sonsonate and Tacuba in Ahuachapán.

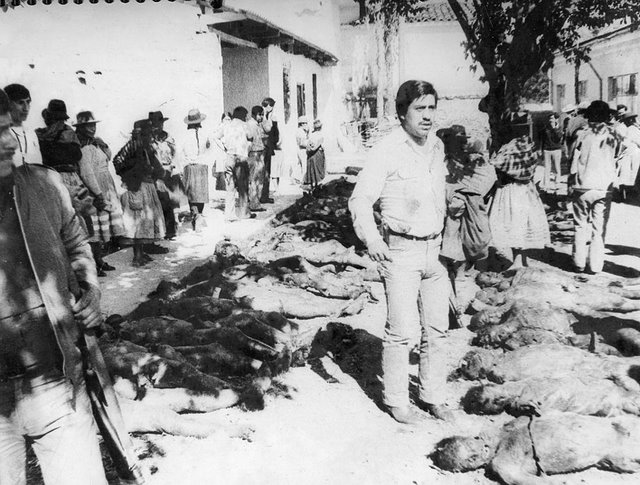

The military counteroffensive quickly defeated the rebels and retook towns that had fallen to the rebels. While an estimated 20 to 30 civilians were killed in the initial revolt, thousands would die in its aftermath. The military along with members of the elite organized into a civic guard and carried out reprisals singling out Indian peasants, those who wore Indian dress, and those with Indian features.

In the town of Izalco groups of 50, including women and children, were shot by firing squads on the outskirts of town. These reprisals would last for about a month after the insurrection. It is estimated that between 8,000 and 30,000 Salvadoran Indians were killed in the aftermath of the insurrection.

In addition to the loss of life suffered by the indigenous community, La Matanza would have other longterm effects. The massacre influenced many Indians to abandon traditional Indian dress, language, and other identifiable cultural traits in many communities in western El Salvador, although recent research has suggested that Indian identity was not completely destroyed.

For the Salvadoran elites the revolt would combine their strong fears of Indian rebellion and communist revolution. When the violence of La Matanza subsided, a combination of racism and anticommunism became the leading ideology of the elite. This ideology served to block social change and to justify repression. Politically, El Salvador would have a series of military juntas until the El Salvador civil war in the 1980s.