|

| The Lebanese Confessional System |

The Lebanese Confessional System refers to the political and legal structuring of the Republic of Lebanon according to religious affiliations. The Lebanese government acknowledges over 17 different religious sects, but the main divide is between Christians and Muslims. The Confessional System was introduced prior to Lebanon's independence during the years of the French mandate (1917–1943).

The French colonial authorities distributed governmental posts based on the population count in the 1932 census, which favored Christians over Muslims in a 6 to 5 ratio. There was not another census for the rest of the century. By the time Lebanon gained independence in 1943, the Lebanese population had become further polarized and identified along confessional lines.

In 1943, the independent Lebanese state enacted the National Pact (Al-Mithaq al-Watani), reinforcing the sectarian system of government by distributing the three top political positions along confessional lines.

|

The national pact is an unwritten agreement and the result of numerous meetings between Lebanon's first president, Bishara al-Khoury (a Maronite Christian), and the first prime minister, Riyad Al-Solh (a Sunni Muslim). Khoury and Solh allocated government posts in a confessional manner in an attempt to please all religious communities and guarantee their participation in the newborn state.

The prime position of president was reserved for Christian Maronites, the post of prime minister was allocated to a Sunni Muslim, the position of speaker of the parliament was allocated to Shi'i Muslims, and the titles of deputy speaker of the house and deputy prime minister went to Greek Orthodox Christians.

The core of the national pact aimed to address the Christians' fear of being overwhelmed by the Muslim communities in Lebanon and the surrounding Arab countries, Syria in particular, and the Muslims' fear of Western hegemony.

In return for the Christian promise not to seek foreign—specifically French—protection and to accept Lebanon's "Arab face," the Muslim side agreed to recognize the independence and legitimacy of the Lebanese state in the 1920 boundaries and to renounce aspirations for union with Syria.

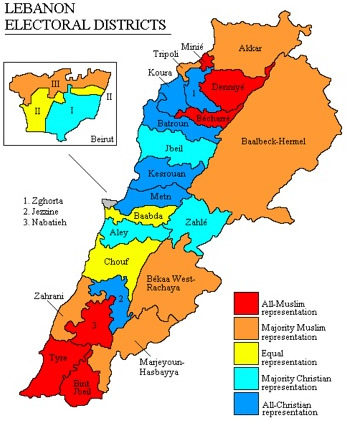

In addition to the national pact, the parliamentary electoral law equally enforced the sectarian system. The representatives in the parliament were divided equally between Christians and Muslims by the Taif Accord, with each sect occupying seats in proportion to the population percentage.

The religious communities represented in parliament, with the number of seats each occupies, is as follows: Maronite Christians (34), Sunni Muslims (27), Shi'i Muslims (27), Greek Orthodox (14), Greek Catholics (8), Druze (8), Armenian Orthodox (5), Alawites (2), Armenian Catholics (1), Protestants (1), and other Christian groups (1).

The confessional system outlined in the national pact was a pragmatic interim to override philosophical divisions between Christian and Muslim leaders at the time of the French withdrawal and independence. However, the frequent political disputes in recent history, the 1958 civil war, and the far bloodier 1975 civil war are testaments to the failure of the national pact to achieve the anticipated social and political integration.