|

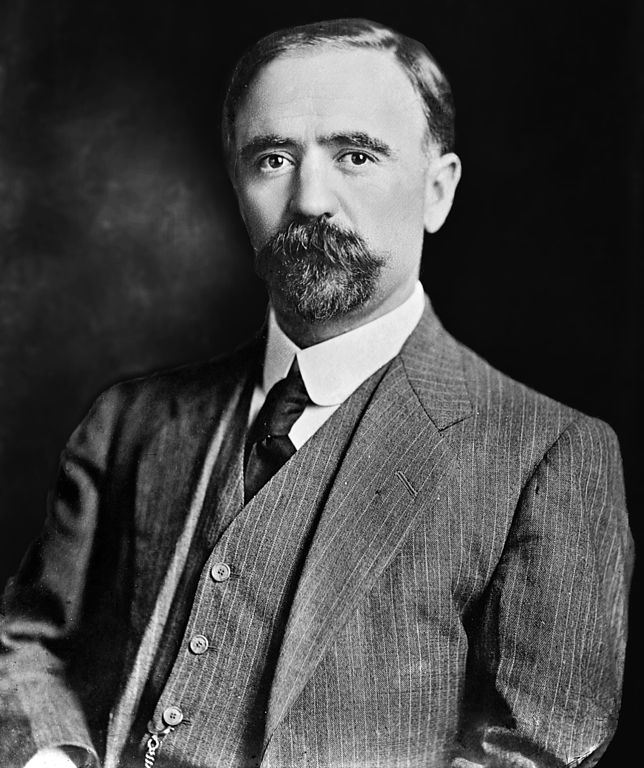

| Francisco Madero |

The president of Mexico from 1911 until 1913, Francisco Indalecio Madero González was a prominent revolutionary who was from one of the richest families in Mexico. He was born on October 30, 1873, at Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, in northeastern Mexico.

His grandfather Evaristo Madero (1828–1911), of Portuguese ancestry, had established massive plantations in the region, becoming fabulously rich and also donating large sums to fund schools and orphanages in the area.

Francisco Madero went to school in Baltimore, Maryland, and then studied in Paris, where he attended the École des Hautes Études Commerciales before studying agriculture at the University of California, Berkeley. Madero came to respect both systems of democracy and was intent on going into politics.

|

In 1904 Madero organized the Benito Juárez Democratic Club, with himself as the president, and they managed to get a candidate elected in the local municipal elections. In 1905 they decided to contest the next election for governor when the incumbent illegally stood for reelection and protests did not succeed in getting him ousted.

In 1908 the Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz announced that he would not stand for reelection. He later decided that he would stand, which was unconstitutional. In 1909 Madero wrote The Presidential Succession of 1910, in which he argued for free and fair elections and that rules to stop incumbents from standing for reelection should be enforced.

This led to the formation of the Mexican Anti-Reelectionist Center, with Madero as cofounder. This movement rapidly gained support, and Madero's enemies decided to preempt the result by having him arrested. Madero was charged with stealing a guayule (a crop used in rubber cultivation).

He evaded the police and managed to make it to the convention of the Anti-Reelectionists, where he was chosen as their candidate for the elections. On the eve of the election, Madero was arrested, as were 6,000 other Anti-Reelectionists. Porfirio Díaz was reelected with 196 votes in the electoral college.

As soon as the elections had ended, after being released on a large bail posted by his father, Madero started a campaign against the reelection of Porfirio Díaz. On October 4, 1910, Madero fled to Laredo, Texas. On November 20, 1910, he managed to persuade the people to take up arms and topple Díaz, who, Madero claimed, had subverted the constitution.

Madero also declared that the elections were null and void. He was a better political speaker than a revolutionary leader, and the small force that he brought with him from the United States into Mexico was routed.

His supporters, mainly drawn from the middle class and upper-class elite, were easily rounded up. This meant that Madero had to get help from many other people, some of whom had been traditional supporters of rebellion against the government, including the men who served Francisco "Pancho" Villa.

At one battle Madero held back from sending his men to attack government soldiers at the border town of Ciudad Juárez, and it was left to Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco to order an assault. At the subsequent Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, signed on May 17, the president's representatives agreed that he would stand down and so end the civil war.

Diaz stood down on May 25, 1911, and Francisco León de la Barra became interim president. In October 1911 a presidential election was held, with Madero standing as presidential candidate. His former vicepresidential running mate, Francisco Váquez Gómez, did not like Madero's plans to stand down the revolutionary forces, and José María Pino Suárez became the new running mate. Madero easily won the elections, and on November 6, 1911, he became president.

As president, Madero introduced many reforms, including the freeing of all political prisoners and the abolition of the death penalty. He also lifted censorship of the press, although this did result in the various factions of his party managing to increase their hostility to each other.

Madero allowed trade unions to organize railway workers, ending the system of giving preference to U.S. workers, and also, through a new department of labor, reduced the workday to a maximum of 10 hours and introduced regulations for the employment of women and children.

His most far-reaching change in the political system was the ending of the jefaturas politicas, party bosses who had controlled various regions, towns, and provinces. They were replaced by nonpolitical municipal authorities who had the tasks of demobilizing the revolutionary soldiers, settling them back into the community, maintaining law and order, and overseeing local and national elections.

In October 1911 Féliz Díaz, the nephew of Porfirio Díaz, staged a revolt to overthrow Madero. In November 1911 Madero became the subject of another rebellion when Emiliano Zapata wanted a considerably more far-reaching agrarian reform program. In addition, some revolutionary soldiers felt that Madero had let them down and had not done enough for his former supporters.

The economy began to stumble, and foreign companies and powerful Mexican business interests began to move against Madero. General Bernardo Reyes staged a third rebellion in December 1911, and Pascual Orozco led a rebellion in January 1912.

Finally, Madero was overthrown in February 1913 when troops led by General Victoriano Huerta fought in the streets for 10 days. Madero was telephoned with the news that his opponents had seized the National Palace and had deposed him, believed to be the first time that a head of state was telephoned to be told of his overthrow. Madero resigned on February 18, 1913, and was executed four days later. He was only 39.