|

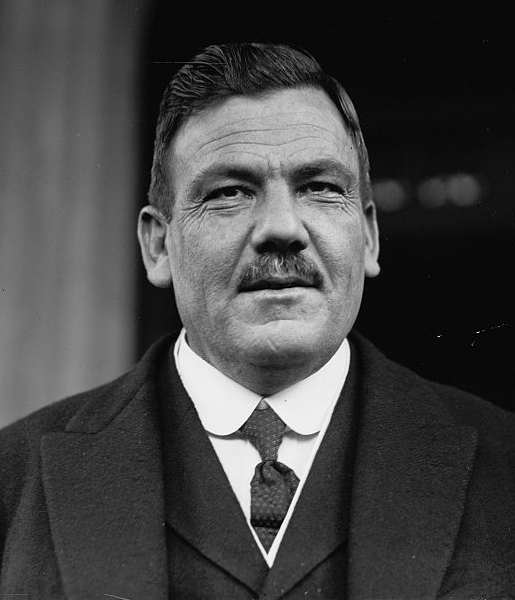

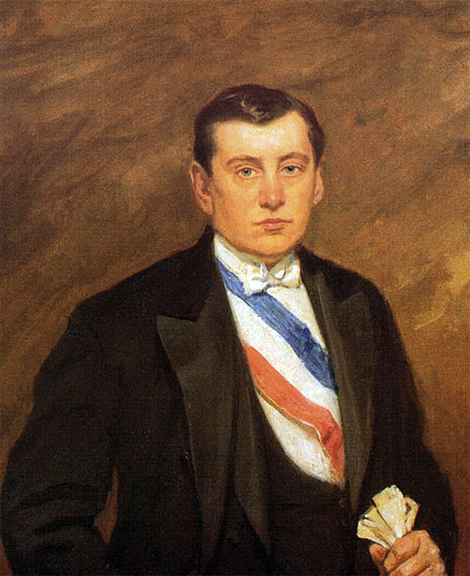

| Arturo Fortunato Alessandri Palma |

Arturo Fortunato Alessandri Palma was president of Chile from 1920 to 1924, again in 1925, and then from 1932 to 1938. During that time he became known as the Lion of Tarapacá. Known initially for his strident support of the poor of Chile, he was later heavily criticized by many of his former supporters when he became far more conservative.

Arturo Alessandri was born on December 20, 1868, at Linares, south of the Chilean capital of Santiago, the son of Pedro Alessandri and Susana Palma. His father's family originally came to Chile from Italy. He was educated at the Sacred Heart School in Santiago, and then he worked at the National Library of Chile. He used his position there to study for a law degree and in 1893 was admitted to the bar.

Politically, Alessandri was connected with the Progressive Club, making him a liberal, and, in fact, he later joined the Liberal Party, becoming secretary of its executive committee in 1890. He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1897 and had six terms in Congress and two terms in the Senate after successfully challenging a prominent local politician for the seat for Tarapacá.

In 1920 Alessandri was elected president of Chile, ending a right-wing domination of Chilean politics that had started in the 1830s. Alessandri faced many problems in office, and to raise more government revenue he introduced income tax for the first time in Chilean history. However, Chile was entering a period of economic hardships, and the new tax only partially made up for the shortfall in the economy.

This came from the fall in the price of nitrate, which saw the Chilean peso fall from one for 27 cents (U.S.) to one for 9 cents. His reform moves were supported by the Liberal Alliance and the Democratic Party, but unemployment rose, and the pay for civil servants and the army fell into arrears.

Furthermore, Alessandri's attempts to spend more on public education, health, and welfare proved unpopular with some sectors of the country. During his time as president from 1920 to 1924, Alessandri had to change his government 16 times until he was finally able to secure a majority in Congress.

However, Congress moved against him, and with the Chilean peso plummeting in value and his inability to pay the army, Alessandri offered to resign. In the end a military junta staged a coup d'état on September 15, 1924. Alessandri fled to the U.S. embassy and then into exile in Europe.

General Luis Altamirano Talavera headed a military junta to run the country, but when it failed to fulfill the social reform program it had promised, junior officers overthrew it and Carlos Ibáñez del Campo headed the new junta.

However, on October 1, 1925, Alessandri was again forced to resign, and Luis Barros Borgono succeeded him. In the elections that followed, Emiliano Figueroa Larraín became president, but he resigned in May 1927 to allow Ibáñez del Campo to return to power.

Ibáñez borrowed U.S. $300 million from the United States and tried to resuscitate the economy. Initially it worked, but Ibáñez was forced from power, and Anarguía Política became president. Elections were held in 1932, and Alessandri was once again elected president.

Alessandri's new administration was totally different from that of the early 1920s. He was a strict constitutionalist, and he had also become more conservative and depended on the support of the right wing.

His economically conservative policies led to his refusing to give money to the poor, especially those hurt by the fall in the price of nitrate and copper. With the depression hurting in Chile, Alessandri tried to reorganize the nitrate industry, doubling the government's share of profits, raising it to 25 percent.

Promoting building and civil engineering projects, Alessandri still wanted to improve the provision of education. The only way of raising the extra money was by using his finance minister, Gustavo Ross Santa María, to tighten up the collecting of taxes.

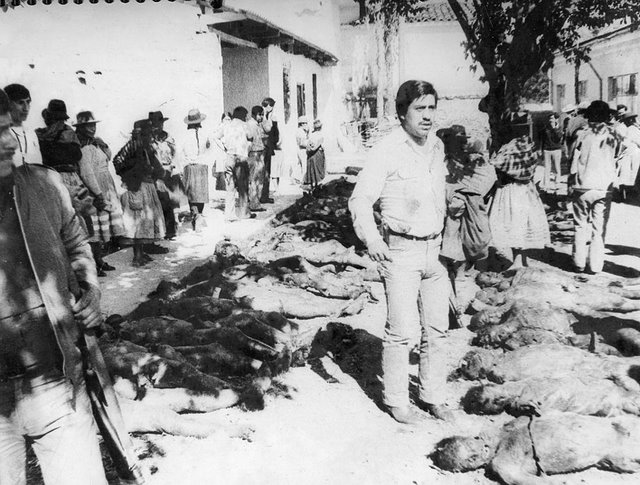

In early 1937 the Nacista movement began to gain support, and on September 5, 1938, it tried to stage a coup d'état to get Ibáñez del Campo back into power. Alessandri had already alienated most of his former supporters, who then formed the Popular Front.

He used the army to arrest Ibáñez del Campo. Alessandri's term as president ended in 1938, and Pedro Aguire Cerda succeeded him. Alessandri went to Europe, endorsing Juan Antonio Ríos Morales in the 1942 elections, which he won.

Returning to Chile, in 1944 Alessandri was elected to the Senate, becoming the speaker in the following year. In the 1946 elections he endorsed Gabriel González Videla, who won. By this time Alessandri had once again become more liberal in his views.

Alessandri towered over Chilean politics, but his speech was often rough and crude. When the U.S. journalist and writer John Gunther visited him, Alessandri's office was decorated with autographed photographs of politicians from all over the world, including Hindenburg, Adolf Hitler, and Edward, prince of Wales (later the duke of Windsor).

He died on August 24, 1950, in Santiago. Jorge Alessandri Rodríguez, who was president of Chile from 1958 until 1964, was Arturo Alessandri's older son. His younger son, Fernando Alessandri Rodríguez, was also active in politics.