|

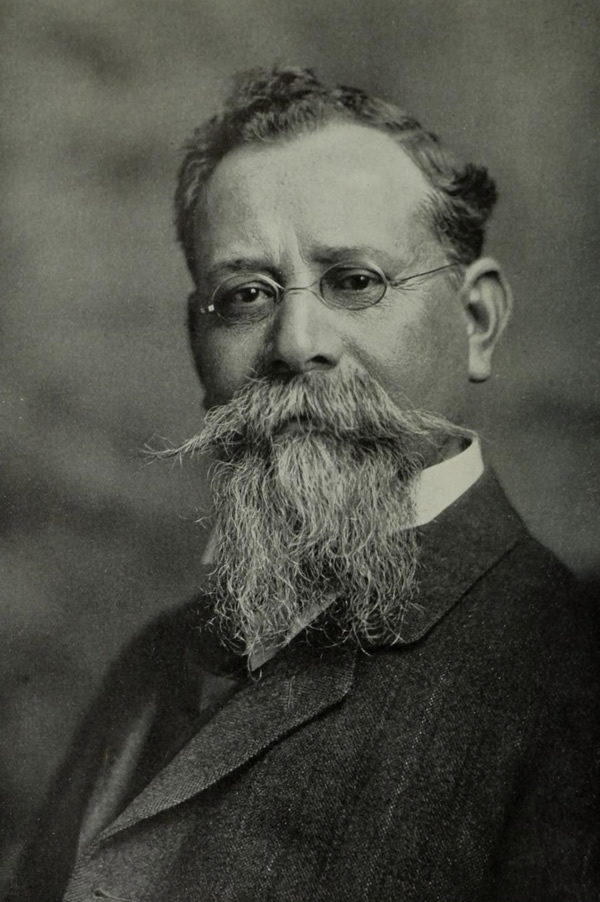

| Venustiano Carranza |

Venustiano Carranza Garza was president of Mexico from 1914 to 1920, having been a supporter of the Mexican Revolution of Francisco Madero. Born on December 29, 1859, at Cuatro Ciénegas, in Coahuila, he was the son of Colonel Jesús Carranza, who had served in the army of Benito Juárez, and María de Jesús Garza.

Carranza was educated at the Ateneo Fuente in Saltillo and then at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, returning to Coahuila, where he took part in running the family farm and ranch. At school he had become interested in Latin American history, and this led him into a late involvement in politics when he became an opponent of Porfirio Díaz, leading a successful revolt against Diaz's handpicked governor of Coahuila.

Carranza, who had been a municipal president, was allowed to retain much of his political power in Coahuila and was also a senator in the national congress. He initially became a supporter of General Bernardo Reyes but quickly came to support the presidential candidate Francisco Madero.

|

Madero was forced to flee into exile in Texas, and from there he rallied his supporters for an attempt to overthrow Díaz. It had been Díaz who had narrowly beaten Madero in the 1910 election, but many, like Carranza, felt that Díaz should not have been allowed to stand, as it went against the Mexican constitution.

Madero became president in November 1911, and Carranza, who had been his secretary of war and of the navy, was appointed governor of Coahuila, where he improved working conditions for people. However, Madero was soon faced with several rebellions against him, and in February 1913 he was overthrown and replaced by General Victoriano Huerta.

Carranza then led a rebellion against Huerta, leading what became known as the Constitutionalist Army, as it supported the reinstatement of Benito Juárez's liberal constitution of 1857.

On May 1, 1915, Carranza became president and immediately tried to continue the reforms introduced by Madero. This included land reform, the formation of a more independent judiciary, and the decentralization of political power. He wanted to control the developing Mexican Revolution by trying to regulate the economic problems facing the country.

Carranza introduced rules to regulate the economy, regulating banks and forcing foreign investors to renounce any diplomatic protection they had previously enjoyed. One of his major targets was the U.S.-owned oil companies, from which the taxation revenue rose 800 percent during Carranza's five years as president.

The government also took over the railways and boosted support for the Compañia Telefónica y Telegrafica Mexicana (CTTM). Although some commentators have seen Carranza as being anti U.S. and seeking to move against foreign companies, he was actually more focused on promoting Mexican industry.

Facing criticism for being too dictatorial, Carranza was eager to prove that his moves were popular, and in November 1916 he held a constitutional convention in Querétaro, which resulted in the 1917 constitution. Carranza felt that it was too radical but agreed to implement it.

It made extensive provisions for education and labor, ensuring that government schools were "free and secular," and limited work to the eight-hour day, with minimum wages, the right to collective bargaining, and the right to strike. In March 1917 special presidential elections were held, and Carranza was reelected.

Carranza became involved in the Plan de San Diego Revolt, whereby Mexican Americans in Texas staged a rebellion that they hoped would bring Texas back under Mexican control. To help, many hundreds of Mexican soldiers, disguised as civilians, crossed into Texas to launch attacks, which ended in October 1915 when the U.S. government recognized Carranza.

In 1916, in answer to attacks across the border by Pancho Villa, the U.S. government sent Brigadier General John J. Pershing with 10,000 soldiers, mainly cavalry, to pursue Pancho Villa into Mexican territory with reluctant help from Carranza. Pershing had to withdraw in February 1917 without capturing Villa.

As well as international problems, Carranza had some immediate trouble from revolutionary insurgents. However, he put a bounty on the head of Emiliano Zapata, who was killed soon afterward. He then turned to grooming Ignacio Bonillas as his successor, but this was to annoy Alvaro Obregón. One of Obregón's men tried to kill Carranza on April 8, 1920, forcing the president to flee Mexico City for Veracruz.

He was deposed on May 7, and on his way to Veracruz, on May 21, in Tlaxcalantongo, in the Sierra Norte of Puebla State, he was assassinated by Rodolfo Herrera. He was succeeded as president by Adolfo de la Huerta, who was president until November, when he was replaced by Alvaro Obregón.