|

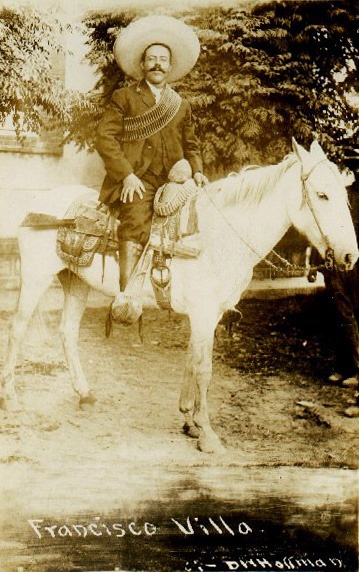

| Francisco “Pancho” Villa |

Francisco "Pancho" Villa was a general in the Mexican Revolution from 1911 until 1920; he commanded troops mostly in the northern part of Mexico. Villa joined an anti-government group in 1910 and started recruiting fighters.

Villa could be vicious and was willing to kill those who opposed him. He also made sure his men were taken care of, which inspired loyalty in them. He was also interested in education and learned to write as an adult.

Born Doroteo Arango in 1878 at Rancho de la Coyotada in the state of Durango, Villa's parents were sharecroppers on a hacienda. Villa worked at the El Gorgojito ranch for a while as a teen. Then at age 13 he shot someone for reasons unknown, fled into the countryside, and became a bandit.

|

During the following 20 years Villa spent time as a bandit and a cattle butcher. There is no clear record of exactly what he did and when. It was during this period that he changed his name to Francisco "Pancho" Villa.

Villa met Abraham Gonzáles in 1910. Gonzáles was working to defeat the reelection of Mexican President José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz in Chihuahua, who was running against Francisco Madero. When Díaz won the election, Madero fled the country and called on his followers to rise up and overthrow Díaz. Díaz was slow to react to events in northern Mexico, where Villa was, and in May 1911 his government collapsed.

Madero was elected president. Madero soon had to fight his own revolution. Villa was unwilling to turn against Madero, who he respected. During the campaign in 1912, Villa ran afoul of General Victoriano Huerta, who had him arrested and almost executed for insubordination. Villa received a reprieve from Madero and instead was jailed.

In December Villa escaped from the prison and made his way to the United States. In February 1913 Huerta, with support from the United States, turned against Madero. He had Madero arrested and shot and then made himself president.

Villa returned to Mexico to fight against Huerta. Throughout 1913 Villa won a number of battles with Huerta's forces and was chosen to command the Division of the North. In December Villa captured Chihuahua and made himself governor.

During 1914 Villa's forces drove south and eventually opened the way for the rebels to march on Mexico City. The fighting had badly damaged the federal army, and seeing that his cause was lost, Huerta resigned on July 15.

An interim president was appointed, but the power was really with the three most powerful chiefs, of whom Venustiano Carranza was named first chief. Villa hated Carranza and spent the remainder of 1914 trying to remove Carranza from power. In December Villa and Emiliano Zapata joined forces to take control of Mexico City.

Villa had Carranza on the run, but instead of finishing Carranza off, Villa chose to not attack directly; Carranza was able to rebuild his army. Villa would be defeated repeatedly in 1915 and pushed farther north by Carranza's rebuilt army.

On July 10 Villa's Division of the North was soundly defeated and ceased to exist. Then, on October 19, with the continued decline of Villa's power, the United States recognized Carranza's government.

On March 9, 1916, Villa led a raid against Columbus, New Mexico. Under pressure from the people of the United States, President Woodrow Wilson launched an expedition led by Brigadier General John Pershing to capture Villa. The expedition was never able to find Villa and nearly caused a war between Mexico and the United States.

Having recovered from the wound he received while fighting Carranza's forces, Villa continued to raid northern Mexican cities controlled by Carranza. When Carranza did not follow through on promised reforms, a rebellion broke out against him.

After Carranza was killed, an offer was made to Villa that if he would lay down his arms, he would be allowed to retire. The negotiations continued until Villa finally agreed to surrender on July 28, 1920. Villa spent the remaining years of his life working the hacienda and making improvements to it.

He added a school, put in a road to the nearby town, and paid for the education of some of the sons of his bodyguards and employees. During his retirement a number of attempts were made to assassinate him, and finally, on July 20, 1923, one succeeded.