|

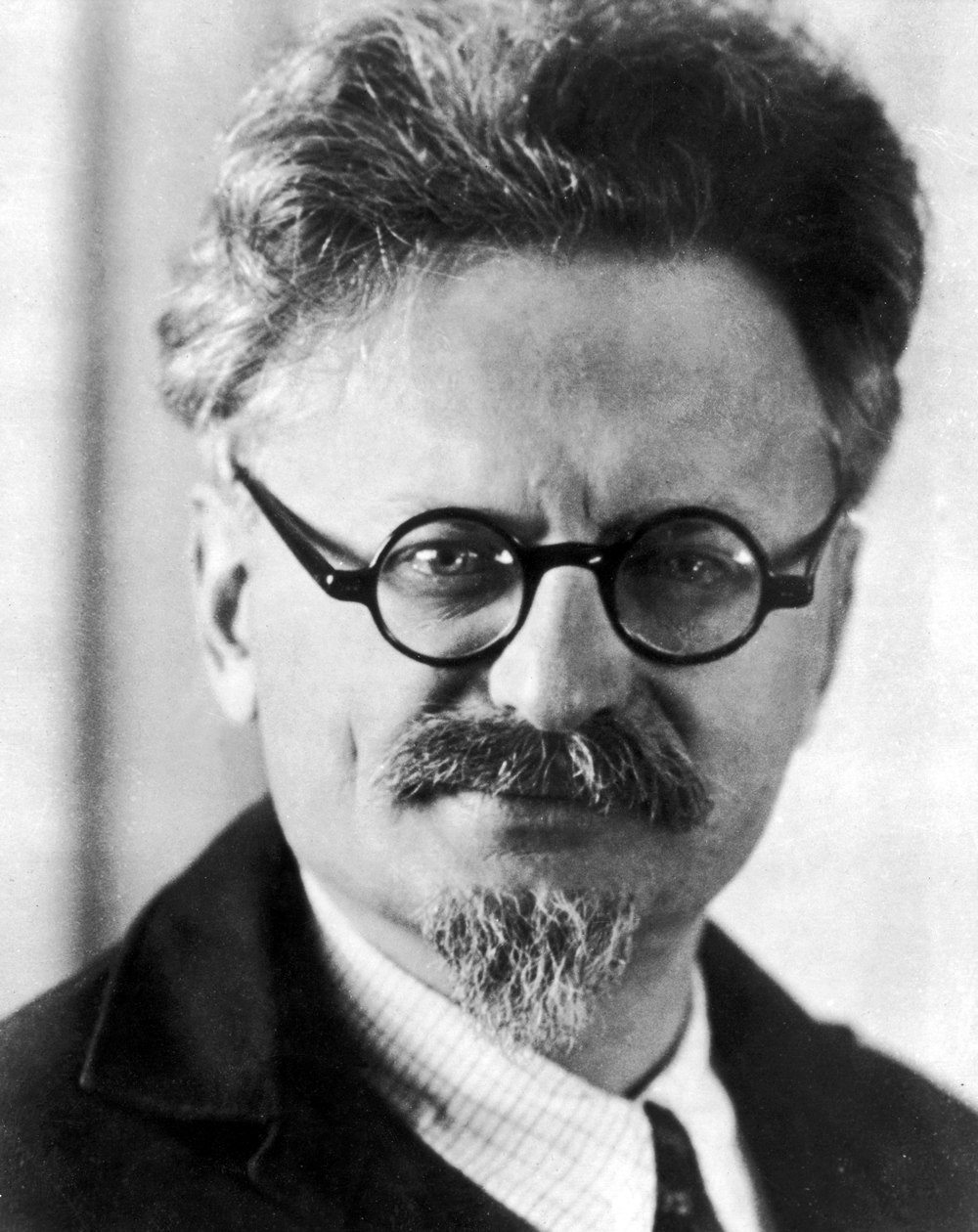

| Leon Trotsky |

Leon Trotsky, born Lev Davidovich Bronstein, was a principal participant in the Russian Revolution of 1917, which brought the Bolsheviks to power. Trotsky was born in the Ukraine to Jewish parents. His father, although illiterate, became a successful farmer and landowner, which enabled Trotsky to attend a good school in Odessa.

In 1896 he became a committed student of Marxism and joined the Social Democratic Party. Because of his political activities he was sent to Siberia in 1898, where he served four years before escaping. He assumed his jailor's name, Trotsky, secured a false passport under that name, and traveled abroad.

Trotsky joined Vladimir Lenin in London and contributed to the revolutionary journal Iskra (spark). After the 1903 split of the Social Democratic Party into Menshevik and Bolshevik factions, Trotsky initially joined the Mensheviks. Upon his return to Russia in 1905, he became active with the St. Petersburg Soviet but again was arrested and sent to Siberia.

|

During that internal exile he developed his notion of permanent revolution

Siberia again failed to hold Trotsky, and he fled to Vienna. He worked as a journalist and between 1907 and 1914 was an editor of Pravda (truth). After the outbreak of World War I, he moved to Switzerland and later Paris, where he continued his agitation until expelled from France. He then went to New York City in early 1917 and along with Nikolai Bukharin and Aleksandra Kollontai worked on the journal Novy Mir (new world).

However, the overthrow of Nicholas II

In November 1917 Lenin made Trotsky the people's commissar for foreign affairs, and he was responsible for negotiating with the Central Powers the humiliating peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ended Russia's participation in World War I.

He then assumed the position of commissar of war in 1918 and was charged with the creation of the Red Army

To resist, Trotsky built a formidable force of 3 million soldiers. His Red Army fought a brutal war on numerous fronts to a successful end and preserved the revolution so that Communist power could be consolidated.

It was during these years that Trotsky clashed over matters of policy with both Joseph Stalin and Lenin. Yet Trotsky was needed, and his harsh suppression of the antiparty Kronstadt Revolt of 1921 brought him back into Lenin's fold. However, Lenin's health was in permanent decline.

Stalin assumed more party roles. He proved himself adept at political intrigue and manipulation, all assets that helped him become general party secretary in 1922. Lenin had reservations about Stalin, but his medical state left him too weak to intervene and save the Soviet Union from a painful dictatorship.

When Lenin died in 1924, power was transferred to a triumvirate of Stalin, Lev Kamenev (Trotsky's brother-in-law), and Gregori Zinoviev. Although Trotsky's Red Army had ensured Communist success, his lack of control of the party apparatus and his failure to gain support in the triumvirate allowed Stalin to isolate him.

As part of this process, he was fired as commissar of war in 1925. Stalin moved to centralize authority in his own hands, and Trotsky and the other members of the triumvirate were a threat to him.

Kamenev and Zinoviev realized the seriousness of the situation and now sought Trotsky's cooperation in an effort to stem Stalin's rise to total power. This effort failed, and Trotsky was removed from the Politburo in 1926 and eventually the party in 1927. Kamenev and Zinoviev were shot in 1936.

Trotsky's fall from grace was not complete, for Stalin still saw him as a major threat to his own authority and in 1928 had him internally exiled to Kazakhstan

Stalin strove to purge the party of all real and imagined Trotsky influences, which led to the great treason trials and purges of 1936–38. In 1936, because of pressure from the government of the Soviet Union, Trotsky was again forced to flee Norway. He moved to Mexico City

In Mexico Trotsky continued his attack on Stalin's perversion of the revolutionary dictatorship, and in 1938 he established with other left-wing followers the Fourth International as a socialist opposition to Stalinism. Because he remained a thorn in Stalin's side, he was viewed as a beacon for espionage. Trotsky's days were clearly numbered.

On August 20, 1940, he was assassinated by Ramon Mercader

He served 20 years for his crime and upon his release lived in Cuba before moving to the Soviet Union, where he became a hero. The Trotsky family, who remained in the Soviet Union, did not survive Stalin's paranoid revenge.

Trotsky blamed Stalin for the deaths of his daughters and son. His brother Alexander, although he renounced Trotsky, was shot in 1938, and his sister Olga, the wife of Kamenev, saw her sons shot in 1936 and was herself murdered in 1941.

Trotsky became an influential 20th-century figure, and his intellectual standing and prolific writings made him a figure of importance in revolutionary circles. He remained a symbol for many extreme left-wing parties in the West who found themselves in opposition to both capitalism and the Soviet brand of communism.