|

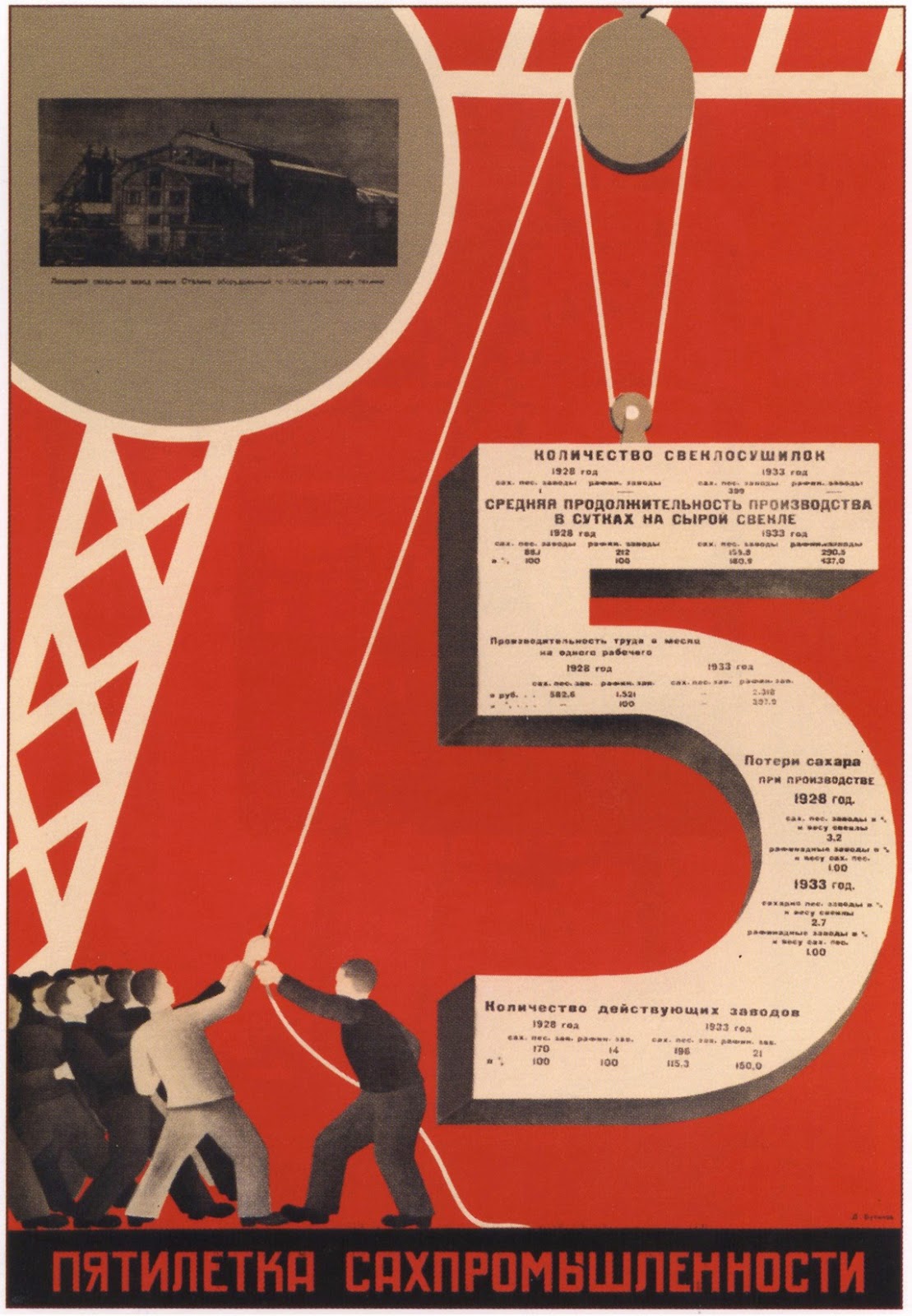

| Soviet five-year plans propaganda poster |

The Five-Year Plans (which existed from 1928 to 1990 with the exception of a break from 1965 to 1971) were the means by which the Soviet Union managed its centralized economy. Using the plans, the Soviet Union devised priorities, assigned resources, determined objectives, and then measured the results.

What is more, the Five-Year Plans were not only used to achieve objectives in a given time period but were the means by which the Soviet government took and maintained complete control over all economic matters.

The Five-Year Plans came into existence in the Soviet Union in the 1920s. In the years after World War II, this method of top-down planning and control was more or less forcibly adopted by the Eastern European nations that came under Soviet control.

|

Starting in 1928, there were 11 Five-Year Plans (1928–32, 1932–37, 1938–42 [interrupted by the beginning of World War II in 1941], 1946–50, 1951–55, 1956–60, 1959–65 [designated the Seven-Year plan], 1971–75, 1976–81, 1981–85, and 1986–90).

Immediately after the revolution of 1917 and through the Russian Civil War, the Soviet leadership attempted to manage the economy through what it referred to as War Communism. All industrial and agricultural enterprises were nationalized by the state to better manage what was produced and distributed. War Communism lasted until 1921, when it was replaced by the New Economic Policy (NEP). NEP represented a significant change in the structure of the economy.

While heavy industry remained under direct state control, smaller concerns could operate on an entrepreneurial basis. It was, essentially, a small-scale, partial return to private enterprise. Farms were not to be appropriated by the state; they had to deliver a tax but could keep the rest to sell or use as they wished.

NEP was extremely popular not only among the citizens who saw its tangible benefits but among a large percentage of the Soviet leadership. There was, however, a faction that believed that the Soviet Union was so far behind the West that NEP was unsatisfactory.

Building the Soviet Union to the point where it could ensure its military, economic, and political survival required effective management of all resources. In addition, as would be made clear by the Stalinist policies of the late 1920s on, exercising control over every aspect of life was considered to be essential.

By 1927, as Jospeh Stalin assumed a more secure position and could begin to impose his policies, NEP's days were numbered. State control would return but in a more effective way than had existed under War Communism. Under this imperative the Five-Year Plans began, the first to be performed from 1928 to 1932.

From the beginning, the Five-Year Plans mainly emphasized heavy industries. First raw materials such as oil, coal, timber, and iron ore had to be extracted. Then factories and even factory cities had to be constructed. The most famous, but not the only one of these, was the city of Magnitogorsk, built to be a major steel producing center.

From these factories and centers, capital goods to manufacture other goods would be made and distributed. Population movements to support these efforts, the construction of roads and railroads, and the building of ships, all to support the industrialization component of the plan, were considered and included.

Lighter industries and consumer goods were assigned a very low priority but were factored in to the plan. Every aspect of economic activity was subject to planning and control, even agriculture, important because although the Soviet Union comprised a huge landmass, only 10 percent of it was suitable for growing crops. The scarcity of food in the years of the civil war through the 1920s was a major source of unrest and possible destabilization.

Each plan was different in that it would emphasize different objectives. In the first two plans (1928 to 1937), creating heavy industry for the Soviet Union was the single most important goal, and all of the plan components were coordinated to support that goal.

In later years, there was an increased emphasis on making consumer goods available to the general population. The plans after World War II focused on rebuilding and repairing the immense destruction that had occurred during the war. In the postwar years, there was once again a very heavy emphasis on increasing agricultural production.

The planning of each Five-Year Plan was a process with defined stages, objectives, and roles to be played by the designated participants. Although planning through the years evolved and each was different, a look at how it was done for the second Five-Year Plan gives a good general sense of how it was done.

In 1931 general work on drafting the second Five-Year Plan began. Each department or industry would develop its targets to be reached during the period under consideration. The State Planning Commission (GOSPLAN) acted as coordinating agency.

It worked with all departments to adjust targets and prepare a cohesive nationwide plan. In preparing the planners would have to take into account the Politburo's grand objective and required resources. The plan's general provisions with substantial detail were completed by early 1933.

In November 1934, the plan received its final approval by the XVII Party Congress. After approval there might be some changes to the plan, but there were no significant departures. In 1935 and 1936, the changes made to the plan were primarily to increase quota quantities to be produced. In this phase, Stalin often took a more or less direct role in encouraging increases in expectations. There were changes to the objectives in 1936 and 1937.

Officially in 1937, the plan came to an end, and the objectives were considered to have been met. Stalin, however, attacked the alleged success of the plan, stating that the goals and objectives were set so low that no satisfaction could be taken from meeting them.

What is significant about this statement is that 1937 was considered to be the worst of the purge years. As perceived political enemies were being rounded up, sabotage and lack of commitment to the fulfillment of the Five-Year Plan was one of the "crimes."

Quotas, or norms, were an integral part of the plans, and the assignment of objectives to an industry or factory percolated down to teams and the individual workers. Meeting one's goals was an important responsibility.

In the prison camps of the Gulag, whether one ate or not would depend on whether one met a norm in construction, cutting timber, or mining gold. Outside the Gulag, however, the rewards for production could result in significant rewards. In 1935 a miner named Stakhanov dramatically increased his team's output by reorganizing its work.

Stakhanov was made into a hero, and workers who excelled in production were known as Stakhanovites. They were rewarded with bonuses and recognition. A significant problem with this, however, was that often, to exceed the goals, the quality declined.

By the mid-1930s, Soviet steel manufacturing capacity was not far behind Germany. There were, however, many problems that existed throughout the existence of the plans. While remarkable progress was made, there were areas in which the plans did not succeed.

Reporting was not always accurate. Inaccuracy was a systemic problem but one that was exploited by managers who could not meet their quotas and so falsified their accomplishments. While the planning was supposed to be coordinated on a national scale, not everything went as intended.

Also, even though everything was theoretically controlled by the state, workers still had a degree of freedom that could make life a nightmare for managers. The workers had to be managed, often with tact and rewards, such as one might have seen in capitalist countries. In the years after World War II, opposition from workers could require sending in the army to use violence to get workers back into the factories.