|

| Social and Cultural Developments in Soviet Society |

Traditionally interpreted in "Western" and "Eastern" (i.e., Soviet and post-Soviet) historiography, the process of social and cultural development of Soviet society reflects the main phases of Soviet societal evolution and all its lacks and advantages.

Strong ideology and total control by Communist Party authorities usually are identified as the main trends in the social and cultural history of Soviet society, and recent years have brought new insight connected with unofficial (underground, or dissident and samizdat) cultural phenomena studies.

The first decade after the October Revolution was a time of transformation of cultural stereotypes connected with the introduction of Marxist-Leninist ideology that demanded revision of mental reference points and human behavior.

|

Milestones of cultural and social revolution of that time were introduced by Vladimir Lenin, among them liquidation of cultural backwardness and illiteracy in the majority of the Soviet Russian population, creation of socialist intelligence, and promotion of Communist ideology.

These ideas were realized step by step through the introduction of a new education system based on new genres of higher and secondary education institutions, through activation of wide publication activity, and in the course of the establishment of tight and sometimes friendly connections with old Russian intelligence.

New tendencies in art and literature appeared at that time, the most striking and well-known of them represented by Kazimir Malevich in painting; Sergei Eisenstein in cinematography; Maxim Gorky, Mikhail Bulgakov, Isaac Babel, and Mikhail Zoschenko in prose; and Anna Akhmatova, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Sergei Yesenin in poetry. These works concentrated mainly on the process of adaptation to the new life among different population groups.

It is worth mentioning that many representatives of the Russian intelligentsia could not adapt to their postrevolution motherland; more than 2 million voluntarily emigrated from the Soviet Union, including composers Sergei Rachmaninoff and Igor Stravinsky; ballerina Anna Pavlova; painters Marc Chagall and Konstantin Korovin; writers Ivan Bunin, Vladimir Nabokov, and Alexander Kuprin; and others whose works have become part of world cultural heritage.

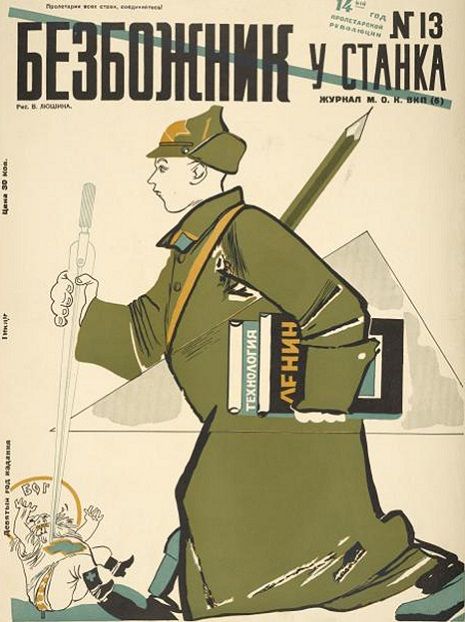

A problem of special importance at that time was relationships with the Orthodox Church, which greatly influenced the mentality of a major part of the population. In February 1918, a law separated the church from the state and schools from the church, which caused fundamental religious opposition led by the patriarch Tikhon. Bolsheviks and church opposition resulted in the plunder of church property and utensils, destruction of churches, repression of church leaders and friars, and broad atheist propaganda.

|

| Soviet antireligious propaganda |

At the period of the New Economic Policy (1921– 27), the politics of korenization implied increasing attention to national minorities, whose language and traditional culture were introduced in Soviet republics.

Reflecting the general liberalization of internal policy inherent to that time, korenization was dismantled with the improvement of the totalitarian system and was replaced by a general tendency toward Russification and repression of minority cultures.

During the period of active promotion of socialism in all spheres of human life, significant results were achieved in the area of social and cultural developments. By 1937 overall elementary education had been introduced in the country, the average level of literacy was already as high as 81 percent, and the task of overall secondary education (in villages, shortened up to seven years) had been put forward as had the necessity of medical service in the country.

The new so-called Stalin Constitution, adopted in 1936, guaranteed Soviet citizens democratic civil rights and freedoms. Nevertheless, its statements in practice were totally ignored by Joseph Stalin, who successfully created a totalitarian system based on the physical destruction of his opponents and competitors.

This tendency was displayed also in the cultural sphere, where artistic works of different genres were evaluated mainly subjectively, and many artists and representatives of science and education were repressed or lost the chance to be published because Stalin did not like their works.

Soviet culture gradually gained a strong ideology based on a new artistic method and style introduced by Nikolay Bukharin and later called socialist realism. Its main idea was that an artist must provide a precise and true picture of real life in its historical development; this picture should be used as an instrument to encourage socialist ideas among working people.

To make control over Soviet artists easier, they were united in hierarchical professional organizations totally controlled by party bureaucracy. Nevertheless, even in this hard situation of ideological control, Soviet writers and poets, composers, and cinematographers enriched world cultural heritage by their works.

The struggle against fascists had caused a revision of the ideological implications of the sociocultural internal policy of the Communist Party. The necessity to maintain a unified Soviet society had resulted in slogans of patriotism, unity, and friendship among all Soviet peoples, and the mass media had actively and effectively contributed to the dissemination of these ideas. Theater, literature, and visual art (also in the form of political placards) were used as potent instruments to maintain the Red Army warriors' inspiration and motivation.

In this situation Stalin even met with the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church, and this fact reflects a general amelioration of party-church relations. Scientific research was concentrated on the improvement of already-existing arms and the creation of the nuclear bomb.

The obvious success of many artists was caused also by the fact that their ideas fit well with the inspirations of the Soviet people. In spite of measures undertaken by the Soviet government to move its most valuable art objects to remote territories or to mask nonportable objects in their places, the cultural heritage in the Soviet Union was seriously damaged during World War II, and many objects were lost for eternity.

Victory over fascism and the general aspirations of the Soviet people had made the World War II the main subject of art in the first postwar decade. At the same time, the destroyed national economy demanded urgent restoration, and this need could be satisfied only by highly educated specialists. Education and science became the subject of special attention in economic development.

At the same time, Stalin started a new phase of totalitarian system improvement that resulted in a new series of repressions and meant the end of the liberalization of ideology. Soon, typical Stalinist forms of culture and society control were restored.

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party and the following dismantling of the personality cult of Stalin following his death caused democratization of social and cultural processes in the Soviet Union and revision of basic ideas, highlighted by literature and art.

Responsibility for past mistakes and comprehension of the lessons of the past have become an important subject of discussion, tightly connected with the general problem of fathers and children. For many recognized representatives of Stalinist culture this process was disastrous, and a series of suicides stressed Soviet intelligence.

Phenomena that were principally new in Soviet culture sprang up, including samizdat (i.e., nonofficially printed literature) produced by Soviet dissidents. Artistic comprehension of repression and Stalinist terror became a striking subject of discussion, and rehabilitation of the works of many repressed writers, artists, and scientists took place during these years.

Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Communist Party and initiator of the dismantling of Stalin's personality cult, actively influenced the cultural process, trying to outline what he saw as appropriate frontiers of mental freedom.

|

| Soviet mechanics |

One of the greatest reformers in the history of Soviet culture, he had inspired the abolition of avant-gardist and abstractionist visual art, including the works of Soviet poet, Jew, and Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky and Boris Pasternak's novel Doctor Zhivago.

General liberalization of life displayed itself mainly in big cities (in the "center"), where the majority of the well-educated population was concentrated. Inhabitants of the countryside, in spite of the political rights and social freedoms proclaimed in the Soviet constitution, could hardly explore them in full measure.

In most cases they could not even move from their villages because they had no official identification documents at their disposal. Even to apply for study at the university in the regional center, they had to ask special permission to get their passports from local Soviet and party authorities.