|

| Algeria |

Algeria remained part of the French Empire throughout the first half of the 20th century, but nationalist movements for independence became increasingly more vocal and determined. Several hundred thousand Algerians fought or worked for the French military during World War I. After the war they expected reforms and changes in French policies of assimilation and favoritism toward the colons, but the colons blocked government reforms announced in 1919.

French government policies dating from the 19th century onward had gradually increased the ownership of the best land by the colons and had resulted in the impoverishment of Algerian peasants. By 1950 most Algerians owned small plots of less than 10 acres.

To survive, peasants became sharecroppers or seasonal workers or fled to the cities where they were generally either day laborers or unemployed. The growing economic and social disparity between the colons and the majority Muslim Algerian population contributed to civil unrest and nationalist discontent.

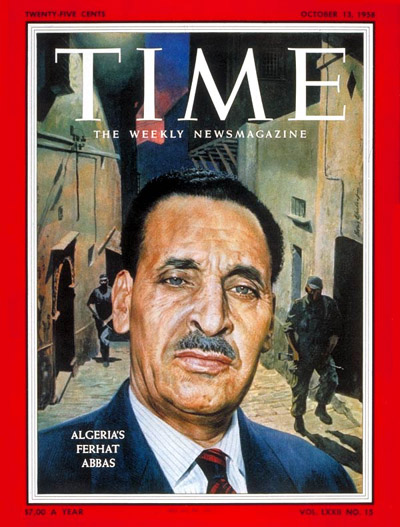

Ferhat Abbas, a pharmacist by profession, represented the first when he said, "If I had discovered an Algerian nation, I would be a nationalist ... I have not found it." Hadj Ben Ahmed Messali championed the second approach, asserting that "Islam is our religion, Algeria our country, Arabic our language." The French often jailed Messali for his uncompromising nationalist stances.

To minimize Algerian opposition, the French adopted a divide and rule tactic by favoring the Muslim Berber population that lived in the mountainous Kabyle region and encouraging it as a separate entity from the Muslim Arab population. These attempts failed as Berbers played key roles in the nationalist movement and were particularly attracted to Messali's approach.

The Algerian Muslim Congress drew up a list of grievances in 1936 but fell far short of advocating complete independence for Algeria. Many Muslim leaders still hoped that a form of assimilation could be devised whereby Muslims could become French citizens without abrogating Islamic law or tradition.

|

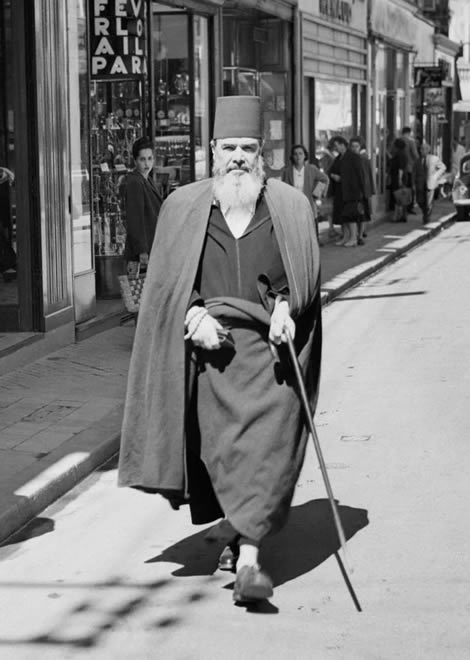

| Messali al-Hajj |

In response to the problem, the Blum-Violette proposals in 1937 provided for the gradual extension of suffrage whereby some 20,000 Algerians would become citizens with more to follow over time.

However, the colons adamantly opposed any reforms that widened Algerian participation and lessened their own political and economic power. The weakness and instability of French regimes in Paris prevented the implementation of reform programs that might have ameliorated the differences.

When the Vichy French regime came to power during World War II, it instituted Nazi racist policies that imperiled both Muslim Algerians and Algerian Jews, who had been granted French citizenship in the late 19th century. These decrees were abolished when the Allied-supported French committee of national liberation took power in 1943.

|

| Ferhat Abbas |

Encouraged by Allied support, Abbas and his supporters issued the Manifesto of Algerian People in 1943. The manifesto paid respect to French culture but noted that assimilation had failed and that reforms were needed. Some French were willing to consider reforms, but others felt that the manifesto would lead to independence and flatly rejected it.

Abbas then formed the Friends of the Manifesto and of Liberty and called for an autonomous republic in Algeria while counseling patience. His movement attracted mostly urban middle-class Algerians. The working class, far greater in numbers, supported Messali's calls for complete independence.

In the spring of 1945 parades in Setif (southwest of Constantine) celebrating the end of World War II in Europe quickly turned into nationalist demonstrations. Violence spread to cities and other areas. In the rioting and French reprisals that quickly followed, hundreds of colons and thousands of Algerians (the figures vary widely ranging from 1,500 to 80,000) were killed.

The Algerian Statute of 1947 in which assimilation was stopped and two separate communities were recognized pleased no one. Under the new law, the French prime minister appointed a governor-general who was assisted by a council of six with the right to apply French law.

The Algerian Assembly was to have two houses, one European and one for "natives." Europeans controlled both houses. Colons were against even this compromise, and Messali responded by demanding complete independence.

|

| Charles de Gaulle in Algeria |

By this time, the majority of Algerians had concluded that the French were never going to grant full equality and that independence was the only solution. By 1950 many Algerian nationalists had either been arrested by the French, were in exile, or had escaped into the mountains of the Kabyle. The conflict remained unresolved until full-scale war broke out in 1954.