|

| Flag of All India Muslim League |

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was established on December 30, 1906, at the time of British colonial rule to protect the interests of Muslims. Later it became the main vehicle through which the demand for a separate homeland for the Muslims was put forth. The Indian National Congress (INC) was perceived by some Muslims as an essentially Hindu

organization where Muslim interests would not be safeguarded.

Formed in the year 1885, the INC did not have any agenda of separate religious identity. Some of its annual sessions were presided over by eminent Muslims like Badruddin Tyabji (1844–1906) and Rahimtulla M. Sayani (1847– 1902).

Certain trends emerged in the late 19th century that convinced a sizable group of Muslims to chart out a separate course. The rise of communalism in the Muslim community began with a revivalist tendency, with Muslims looking to the history of Arabs as well as the

Delhi sultanate and the Moghul rule of India with pride and glory.

Although the conditions of the Muslims were not the same all over the

British Empire, there was a general backwardness in commerce and education. The British policy of "divide and rule" encouraged certain sections of the Muslim

population to remain away from mainstream politics.

The INC, although secular in outlook, was not able to contain the spread of communalism among Hindus and Muslims alike. The rise of Hindu militancy, the cow protection movement, the use of religious symbols, and so on alienated the Muslims. Syed Ahmed Khan's (1817–98) ideology and political activities provided a backdrop for the separatist tendency among the Muslims. He exhorted that the interests of Hindus and Muslims were divergent.

Khan advocated loyalty to the British Empire. The viceroy Lord Curzon (1899–1905) partitioned the province of Bengal in October 1905, creating a Muslim majority province in the eastern wing. The INC's opposition and the consequent swadeshi (indigenous) movement convinced some Muslim elites that the congress was against the interests of the Muslim community.

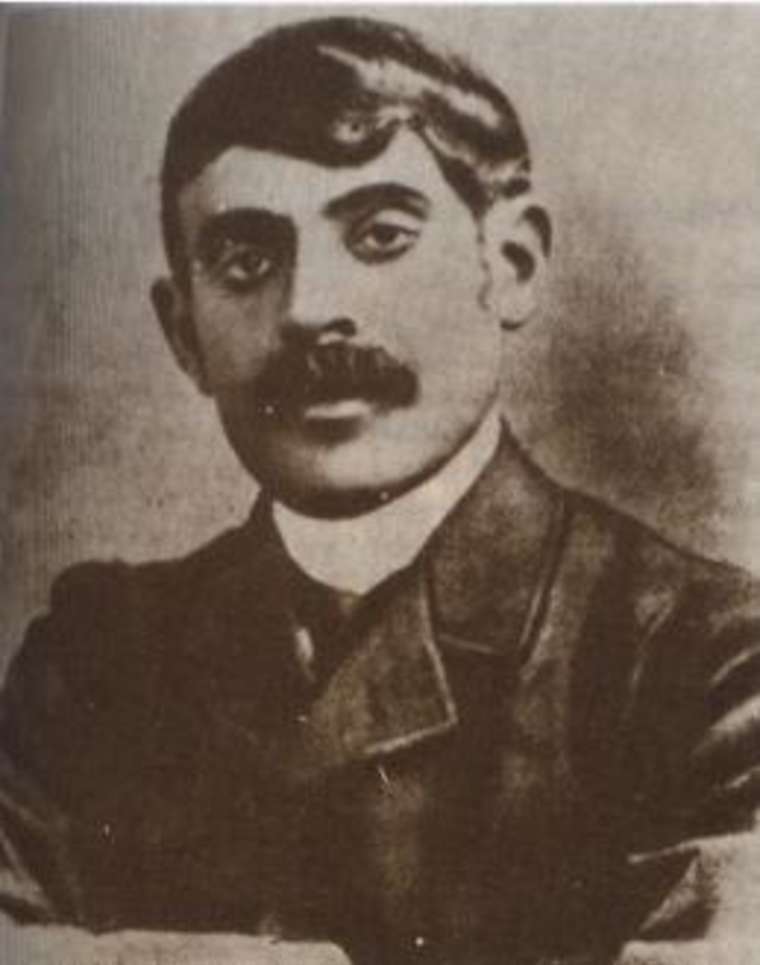

A pro-partition campaign was begun by the nawab of Dhaka, Khwaja Salimullah Khan (1871–1915), who had been promised a huge amount of interest-free loans by Curzon. He would be influential in the new state. The nawab began to form associations, safeguarding the interests of the Bengali Muslims. He was also thinking in terms of an all-India body. In his Shahbag residence he hosted 2,000 Muslims between December 27 and 30, 1906.

|

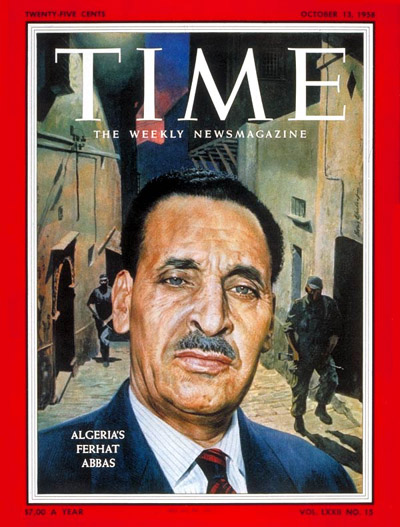

| At the All India Muslim League Working Committee, Lahore session, March 1940 |

Sultan Muhammad Shah, the Aga Khan III (1877– 1957), who had led a delegation in October 1906 to

Viceroy Lord Minto (1845–1914) for a separate electorate for the Muslims, was also with Salimullah Khan. Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk (1837–1907) of the Aligarh movement also was present in Dhaka. On December 30 the AIML was formed.

The chairperson of the Dhaka conclave, Nawab Viqar-ul-Mulk (1841–1917), declared that the league would remain loyal to the British and would work for the interests of the Muslims. The constitution of the league, the Green Book, was drafted by Maulana Muhammad Ali Jouhar (1878–1931).

The headquarters of the league was set up in Aligarh (Lucknow from 1910), and Aga Khan was elected the first president. Thus, a separate all-India platform was created to voice the grievances of the Muslims and contain the growing influence of the Congress Party. The AIML had a membership of 400, and a branch was set up in London two years afterward by Syed Ameer Ali (1849–1928).

The league was dominated by landed aristocracy and civil servants of the United Provinces. In its initial years it passed pious resolutions. The leadership had remained loyal to the British Empire, and the Government of India Act of 1909 granted separate electorates to the Muslims.

A sizable number of Muslim intellectuals advocated a course of agitation in light of the annulment of the partition of Bengal in 1911. Two years afterward the league demanded self-government in its constitution. There was also change in leadership of the league after the resignation of President Aga Khan in 1913.

Mohammad Ali Jinnah (1876–1948), the eminent lawyer from Bombay (now Mumbai), joined the league.

Driving Out the British

Hailed as the ambassador of "Hindu-Muslim unity," Jinnah was an active member of the INC. He still believed in cooperation between the two communities to drive out the British. He became the president of the AIML in 1916 when it met in Lucknow. He was also president between 1920 and 1930 and again from 1937 to 1947.

Jinnah was instrumental in the Lucknow Pact of 1916 between the congress and the league, which assigned 30 percent of provincial council seats to Muslims. But there was a gradual parting of the ways between the INC and the AIML. The appearance of

Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869–1948) on the Indian scene further increased the distance, as Jinnah did not like Gandhi's noncooperation movement.

The short-lived hope of rapprochement between the two parties occurred in the wake of the coming of the Simon Commission. The congress accepted the league's demand for one-third representation in the central legislature. But the

Hindu Mahasabha, established in 1915, rejected the demand at the All Parties Conference of 1928. The conference also asked

Motilal Nehru (1861–1931) to prepare a constitution for a free India.

The Nehru Report spelled out a dominion status for India. The report was opposed by the radical wing of the INC, which was led by Motilal's son

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964). The league also rejected the Nehru Report as it did not concede to all the league's demands. Jinnah called it a parting of the ways, and the relations between the league and the congress began to sour.

The league demanded separate electorates and reservation of seats for the Muslims. From the 1920s on the league itself was not a mass-based party. In 1928 in the presidency of Bombay it had only 71 members. In Bengal and the Punjab, the two Muslim majority provinces, the unionists and the Praja Krushsk Party, respectively, were powerful.

League membership also did not increase substantially. In 1922 it had a membership of 1,093, and after five years it increased only to 1,330. Even in the historic 1930 session, when the demand for a separate Muslim state was made by President Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938), it lacked a quorum, with only 75 members present.

After coming back from London, Jinnah again took the mantle of leadership of the league. The British had agreed to give major power to elected provincial legislatures per the 1935 Government of India Act. The INC was victorious in general constituencies but did not perform well in Muslim constituencies.

Many Muslims had subscribed to the INC's ideal of secularism. It seemed that the two-nation theory, exhorting that the Hindus and Muslims form two different nations, did not appeal to all the Muslims. The Muslims were considered a nation with a common language, history, and religion according to the two-nation theory.

In 1933 a group of Cambridge students led by Choudhary Rahmat Ali (1897–1951) had coined the term Pakistan (land of the pure), taking letters from Muslim majority areas: Punjab P, Afghania (North-West Frontier Province) A, Kashmir K, Indus-Sind IS, and Baluchistan TAN. The league did not achieve its dream of a separate homeland for the Muslims until 1947.

It had been an elite

organization without a mass base, and Jinnah took measures to popularize it. The membership fees were reduced, committees were formed at district and provincial levels, socioeconomic content was put in the party manifesto, and a vigorous anti-congress campaign was launched. The scenario changed completely for the league when in the famous Lahore session the Pakistan Resolution was adopted on March 23, 1940.

Jinnah reiterated the two-nation theory highlighting the social, political, economic, and cultural differences of the two communities. The resolution envisaged an independent Muslim state consisting of Sindh, the Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province, and Bengal. The efforts of Jinnah after the debacle in the 1937 election paid dividends as 100,000 joined the league in the same year.

There was no turning back for the league after the

Pakistan Resolution. The league followed a policy of cooperation with the British government and did not support the Quit India movement of August 1942. The league was determined to have a separate Muslim state, whereas the congress was opposed to the idea of partition.

Reconciliation was not possible, and talks between Gandhi and Jinnah for a united India in September 1944 failed. After the end of

World War II, Great Britain did not have the economic or political resources to hold the British Empire in India. It decided to leave India finally and ordered elections to central and provincial legislatures.

The league won all 30 seats reserved for Muslims with 86 percent of the votes in the elections of December 1945 for the center. The congress captured all the general seats with 91 percent of the votes. In the provincial elections of February 1946, the league won 440 seats reserved for Muslims out of a total of 495 with 75 percent of the votes.

Flush with

success, the Muslim members gathered in April for the Delhi convention and demanded a sovereign state and two constitution-making bodies. Jinnah addressed the gathering, saying that Pakistan should be established without delay.

It would consist of the Muslim majority areas of Bengal and Assam in the east and the Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province, Sind, and Baluchistan in the west. The British government had dispatched a cabinet mission in March to transfer power. The league accepted the plan of the cabinet mission, but the league working committee in July withdrew its earlier acceptance and called for a Direct Action Day on August 16.

The league joined the interim government in October but decided not to attend the Constituent Assembly. In January 1947 the Muslim League launched a "direct action" against the non–Muslim League government of Khizr Hayat Tiwana (1900–75) of the Punjab.

Partition was inevitable, and the new viceroy,

Lord Louis Mountbatten (1900–79), began to talk with leaders from the league as well as the congress to work out a compromise formula. On June 3, 1947, it was announced that India and

Pakistan would be granted independence.

The Indian Independence Act was passed by the British parliament in July, and the deadline was set for midnight on August 14–15. The demand of the league for a separate state was realized when the Islamic Republic of Pakistan was born on August 14.

On August 15 Jinnah was sworn in as the first governor-general of Pakistan, and Liaqat Ali Khan (1895–1951) became the prime minister. The new nation had 60 million Muslims in East Bengal, West Punjab, Sind, the North-West Frontier Province, and Baluchistan.

After independence the league did not remain a major political force for long, and dissent resulted in many splinter groups. The Pakistan Muslim League had no connection with the original league. In India the Indian Union Muslim League was set up in March 1948 with a stronghold in the southern province of Kerala.

The two-nation theory received a severe jolt when East Pakistan seceded after a liberation struggle against the oppressive regime of the west. A new state,

Bangladesh, emerged in December 1971. In the early 21st century more Muslims resided in India (175 million) than in Pakistan (159 million).