|

| Oil Industry in the Middle East |

During the 20th century oil became a major revenue source for a number of Middle Eastern nations. The first petroleum concession was signed between the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) and the Qajar shah of Iran in 1901.

An Australian, William Knox D'Arcy, negotiated the contract, whereby the shah and the grand vizier received 50,000 shares as a gift. The government was to receive 16 percent of the profits after costs were subtracted.

The contract was to last for 60 years, the company was to pay no taxes, and the prospecting covered 500,000 square miles, or five-sixths, of Iran. The British government owned half of Anglo-Iranian Oil, Burmah Oil owned 22 percent, and the rest was owned by a combination of investors.

|

The company justified the extremely favorable terms on the grounds that at the time, prospecting for oil was extremely risky and capital intensive. Dozens of wells might be drilled at great expense before oil was found. Reza Shah managed to obtain better terms after he revoked the first concession in 1932.

The first contract set the pattern for future ones in the region for the next half century. The petroleum industry was a vertical and horizontal monopoly. Western companies controlled the prospecting, sources, transport, refining, and sale of oil. Seven major corporations, or the so-called "seven sisters," eventually dominated the industry.

These were Standard Oil of New Jersey (founded by John Rockefeller), Royal Dutch Shell, British Petroleum, Gulf, Socony-Mobil, Texaco, and Standard Oil of California. Compagnie Française des Petroles (CFP) and an Italian company were smaller firms. Many of these companies had overlapping ownerships and directors.

Middle East governments were too weak, lacked the technology to develop the industry themselves, and willingly granted concessions giving Western companies control over their vital natural resource. With no private ownership of oil fields in the Middle East, revenues from oil went directly to the governments to be spent as each deemed appropriate.

Because the oil was purchased primarily in Western nations for industrial, military, and transport use, the resource did not generate many jobs or secondary industries in the Middle East, unlike, for example, the automotive industry in the West, which created numerous secondary industries.

The second major concession in the Middle East was signed between Iraq and a consortium of Western companies. Calouste Gulbenkian negotiated the contract in exchange for 5 percent of the shares. As a result of this deal, Gulbenkian was dubbed "Mr. Five Percent" and became one of the richest men in the world at the time.

Ownership of the company was apportioned as follows: 25 percent D'Arcy, comprising Burmah and the British government and that became known as British Petroleum (BP); 25 percent CFP, of which the French government owned 40 percent; 25 percent Royal Dutch Shell, comprising British and Dutch interests; and 25 percent U.S. gas, including Standard Oil of New Jersey and Socony Mobil.

|

These firms divided payment of the 5 percent for Gulbenkian evenly among themselves. The contract covered all of Iraq for 75 years, allowed for no taxation of the companies, and established a set payment amount per ton. Revenues to oil-producing nations did not increase with prices that were set by the oil companies.

A New Zealander, Frank Holmes, obtained the concession in Bahrain in 1925, and U.S. companies bought into that concession. Holmes also negotiated with Kuwait for a concession there, but production in Kuwait did not begin until 1945.

Standard Oil of California initiated negotiations with King Abd al-Aziz Ibn Saud in Saudi Arabia and obtained a concession there in 1933 under the California Arabian Standard Oil Company that was to pay the Saudi Arabian government a set amount in gold sovereigns.

During the Great Depression the payment was renegotiated for dollars or sterling. During the 1940s additional investments by U.S. oil firms were made, and the company became the Arabian-American Oil Company (ARAMCO).

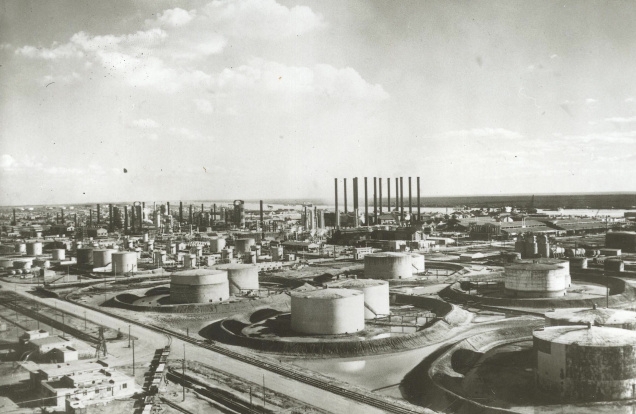

Ownership of ARAMCO was divided among Standard Oil of California (30 percent), Texaco (30 percent), Standard Oil of New York (30 percent), and Socony Mobil (10 percent). With assistance from the U.S. government, ARAMCO built a refinery and extensive facilities for the company and its employees in Ras Tanura.

ARAMCO agreed to a 50-50 split with Saudi Arabia rather than paying the 50 percent corporate taxes in the United States in 1950. Other companies, which did not enjoy the same tax benefits from their nations, were reluctantly forced to follow suit.

By 1950 Middle East oil holdings were apportioned along the following lines: AIOC in Iran, Iraq, Mosul, Basra Petroleum companies (IPC) in Iraq, ARAMCO in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait Oil Company in Kuwait, Bahrain Petroleum Company in Bahrain, and Petroleum Development Ltd. (IPC) in Qatar.

However, oil production and revenues in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states did not begin to soar until the 1960s and 1970s as demand from industrialized Western nations and Japan steadily escalated.