|

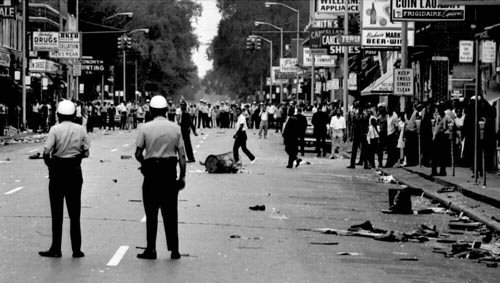

| Race Riots |

Segregation is physical separation based on race, gender, class, or religion. It can occur by law (de jure) or by actual practice (de facto). It may be voluntary, involuntary, or somewhere between the two. In the U.S. context, segregation historically has meant the separation of blacks involuntarily from white society.

In the antebellum United States, the North and cities in the South were more segregated than was the rural South, where an agricultural economy based on plantations and farms reduced opportunities or incentives for segregation. Northern segregation became more pronounced in the 1820s through the 1840s due to the large European immigration and the increase in white male voting.

Northern urban segregation was occasionally de jure, but usually it was due to white preference. Blacks were removed from jobs, schools, public accommodations, churches, neighborhoods, and voting booths. Blacks responded by creating their own churches, lodges, and communities.

|

In the South the plantation economy required a large labor force—mostly slave. Slaves, it was thought, were better kept behind the big house where they could be observed than in towns or elsewhere where they might plot against the white near-minority. Free and slave blacks had access to churches, theaters, and other facilities, but only in their own sections. Blacks and whites did not ordinarily mingle. Schools and social welfare were forbidden to blacks.

After the Civil War, the South developed de facto segregation similar to that of the antebellum North. The key concept was separate but equal. Prisons were segregated, as were militia units, cemeteries, trains and boats, streetcars, and general public accommodations. Blacks initially accepted separate but equal, however unequal, as superior to having no access at all.

Where segregated institutions were totally inadequate, as they had in the North, southern blacks developed their own segregated facilities. Residential segregation developed as freedmen left the plantations for freedmen's camps, the outskirts of cities, and rural black communities.

After Reconstruction, Redeemer governments abandoned all pretense of equality. The approach was validated by Plessey v. Ferguson (1896), and for decades the courts ruled against black efforts to mitigate if not overturn segregation.

Only in Buchanan v. Warley (1917), a residential segregation case, did blacks win a victory against segregation. Even that ruling was overwhelmed by white prejudice and a limited amount of black preference that combined to segregate most U.S. neighborhoods. Where blacks and whites integrated, usually both were poor.

|

| U.S. Racial Segregation |

In the North, Reconstruction meant that black voters had a voice. Most jurisdictions abandoned de jure segregation, but de facto segregation was similar to that in southern cities. Residential areas were segregated, and so were job sites. Some accommodations were off limits not by law but by custom.

The great migration of blacks northward after the turn of the century and particularly during and after World War I led to competition and conflict between black migrants and old-time and immigrant whites for jobs, housing, and other basics of life. Blacks became restricted to urban ghettos with their own schools, facilities, and business districts. By the 1920s segregation in the North and South was comparable.

When the federal government instituted a laissez faire policy regarding states' treatment of their black populations after Reconstruction, the states implemented disenfranchisement, discrimination, and peonage. Blacks without rights were second-class citizens.

|

White supremacy generated race hatred and lawlessness, and the result was a massive outbreak of lynching. Although lynching occurred throughout the United States and involved whites as well as blacks, it was predominantly a southern act against blacks. Between 1882 and 1951, of the 4,730 persons lynched, 3,437 were black.

The shift began in the decade prior to World War I. Rather than attacking an individual, white mobs began attacking entire communities. Wanting to preserve white power and vent frustrations against the helpless, white mobs went into black neighborhoods, beat and killed large numbers of blacks, and damaged a great deal of black property. Blacks commonly fought back, but the preponderance of casualties were black. Because the North was more urbanized than the South, most riots occurred in the North.

Blacks began migrating to northern cities as the South's segregation became tighter and urban industrialization offered alternative employment to debt peonage on southern farms. Blacks seemed a threat to northern white jobs and neighborhoods. World War I exacerbated the situation, and it also raised the specter of black soldiers returning and refusing to accept second-class citizenship.

The summer of 1919 saw 26 race riots, not only in Chicago and Washington, D.C., but in such cities as Charleston, South Carolina; Longview, Texas; Omaha, Nebraska; and Elaine, Arkansas. Black deaths exceeded 100, injuries were in the thousands, and thousands more were left homeless.

The most serious riots were in Wilmington, North Carolina (1898); Atlanta, Georgia (1906); Springfield, Illinois (1908); East St. Louis, Illinois (1917); Chicago, Illinois (1919); Tulsa, Oklahoma (1921); and Detroit, Michigan (1943).

Wilmington's riot was the first major outbreak since Reconstruction. An election rife with fraud and intimidation of black voters produced a white racist city administration resolved to control the city's black population.

Whites began rampaging two days after the election, killing about 30 blacks and forcing many others to leave. The Atlanta riot of 1906 occurred after months of inflammatory press treatment of black crime in an effort to disenfranchise blacks.

|

| Segregation era |

Reports that 12 white women were raped in a week provoked a white riot. White mobs murdered blacks, destroyed homes and businesses, and overwhelmed police and black resistance. After four days, 10 blacks and two whites were dead, and hundreds were injured. Over 1,000 left Atlanta.

The rioters in Springfield, Illinois, reacted to a white woman's claim that she had been molested by a black man. After lynching the alleged attacker, the crowd began dragging blacks from homes and streetcars.

The National Guard restored order only after four whites and two blacks had been killed. White liberals, shocked by the violence in the hometown of Abraham Lincoln, met the next year with blacks and formed the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).

Illinois was the scene of another riot in 1917 in East St. Louis. White workers feared black competition for jobs and attendant status. An aluminum plant brought in black and white strike breakers and, with militia and court injunctions, broke a white strike. The union blamed the blacks.

The result was a riot, including beatings and destruction of property. After the riot, harassment and beatings continued for several months. In June a new riot began, and this time, along with the beatings, burnings, and the destruction of over 300 buildings, the official death toll was nine whites and 39 blacks.

Chicago's riot was the worst in the postwar years. A black swimmer entered the whites-only section of the water, leading white swimmers to stone him until he drowned; 13 days of rioting by thousands of blacks and whites produced 15 white and 23 black deaths and 178 white and 342 black injuries. Property destruction left over 1,000 families homeless.

The Tulsa riot was in response to a white girl's allegation that a black man had attempted to rape her in a public elevator. Rumors that the suspect was to be lynched led an armed black mob to the jail. Whites and blacks fought, and the riot was under way.

A mob of over 10,000 rampaged through the black neighborhood. Machine guns and airplanes were used to help the white mob, and by the time four companies of the National Guard had restored order, 150 to 200 blacks were dead.

Rioting eased after that, but World War II brought a massive black migration to the war jobs of the nation's cities. Detroit's blacks and whites competed for the same jobs and the same houses. On June 20, 1943, fighting began in an integrated recreational area, Belle Isle.

Fighting became rioting, with the customary looting and burning of the black neighborhoods. The white mobs spread through the city seeking blacks downtown as well as in the ghettos. Cars full of whites were shot at by black snipers. Federal troops quelled the riots, but 25 blacks and nine whites were dead.

The riots inevitably started when whites attacked blacks. This occurred at times of social dislocation. Riots grew due to the spread of rumors. The police consistently either were a precipitating factor or assisted in the growth of the riots.

The location of the riots was always in the black community. Blacks reacted to white violence either by retaliating violently, leaving the cities, or engaging in peaceful protest. The NAACP publicized the riots and continued to work for legislative reform.

World War II altered the civil rights landscape. The NAACP had won a series of victories from the 1920s, slowly tearing down the legal structure supporting unequal facilities. The Supreme Court overturned the white primary in 1944, making black access to the political process theoretically possible. Between 1940 and 1952 southern black voter registration rose from 150,000 to over 1 million.