|

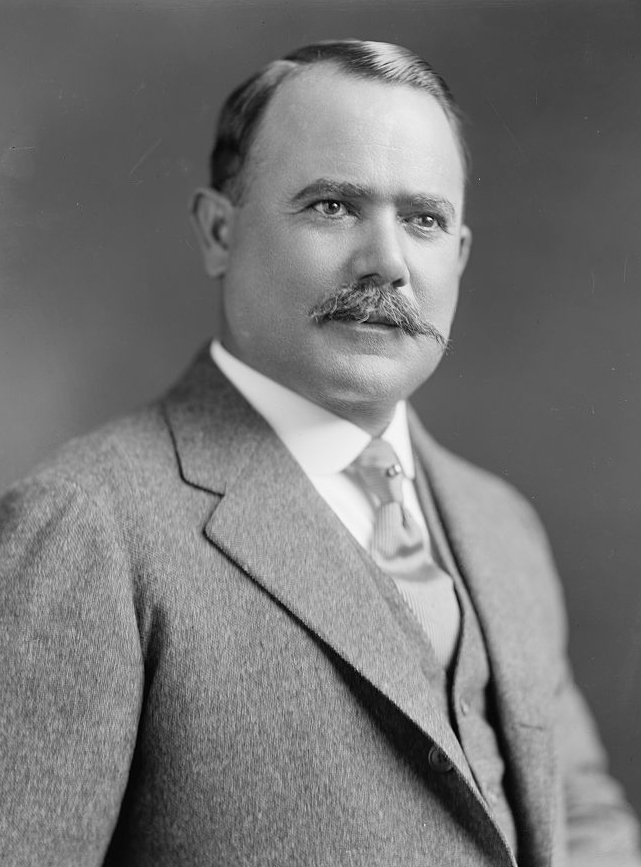

| Álvaro Obregón |

The president of Mexico from 1920 until 1924, General Álvaro Obregón Salido was born on February 19, 1880, at the Hacienda de Siquisiva in southern Sonora, in the far northwest of Mexico. The 17th son of Francisco Obregón, who died when Álvaro was young, and Cenobia Salido, it is often claimed that his name was derived from the Irish surname O'Brian. In later life Obregón used to joke that he had so many older brothers and sisters that when the family ate Gruyère cheese only the holes were left for him.

Obregón did not take part in politics when he was young and stayed away from the clashes during the Mexican Revolution. He spent this time working on the family farm and was said to have learned the Mayan language during this period, although some biographers claim that he could only speak a few words. He developed skills including carpentry and photography.

In 1911 Álvaro Obregón entered politics, being elected mayor of Huatabampo. He was a supporter of the then president, Francisco Madero, who was facing four separate revolts. Madero was captured and executed by two of the rebel leaders, Félix Díaz, nephew of a former longtime president, and General Victoriano Huerta.

|

Huerta was an unpopular president, and Obregón joined a revolt led by Venustiano Carranza, which overthrew him. With Carranza in power, there were also clashes between the new government's forces and those of Pancho Villa. Obregón, aided by General Benjamin Hill, led the federal troops on April 6–7, 1915, when they defeated Villa's men.

In a battle that lasted from April 29 to June 5, Obregón again defeated Villa but lost his right arm to a grenade. On July 10 in the next engagement of what became collectively known as the Battle of Celaya, Obregón's men prevailed again.

Obregón had hoped to succeed Carranza when the presidency became vacant in 1920 and was angered when Carranza named Ignacio Bonillas as his successor. This caused Obregón to plan a military revolt to put himself into power.

Carranza was deposed and killed in May 1920 and was replaced by Adolfo de la Huerta, who was provisional president until elections could be held. After the elections, which Obregón won, de la Huerta stepped down, and Obregón became president of Mexico.

De la Huerta had done much to reduce the fighting in the country, and most of the country was, for the first time in many years, at peace. This situation allowed for more money to be spent on education than on defense. When rebellions did break out, they were quickly crushed, and their leaders were killed.

Although the four years of Obregón's presidency saw further land and agrarian reforms and moves to reduce the power of the Roman Catholic Church, Obregón changed Carranza's hostile approach to the United States to one of establishing better trade and diplomatic relations.

When he became president, the U.S. government did not extend recognition to his regime. This initial problem was made worse by the death of a U.S. citizen, Rosalie Evans, who was killed defending her farm from the governor of Puebla, JoséMaría Sánchez.

In summer 1923, talks began between Mexican and U.S. representatives and led to the Bucareli Accords, by which the Mexican government rolled back some of the measures that had been introduced by the revolutionaries. Some senators denounced it as going back on fundamental promises made by current and previous administrations.

In heated debate the accords were denounced in both the Mexican senate and the chamber of deputies. However, in September 1923 the U.S. government formally recognized Obregón as president of Mexico. Trade increased quickly, especially with the improved sale of Mexican petroleum to the United States.

Obregón's main reason for overthrowing Carranza had been the latter's choice of an heir apparent. This was also going to cause Obregón trouble. He chose Plutarco Calles as his successor, but Adolfo de la Huerta contested this, leading a revolt in December 1923.

With U.S. support for his government, Obregón prevented guns from being sold to the rebels, and the rebellion fizzled out, but not before they had killed one of Obregón's allies, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, the governor of Yucatán. Obregón was able to step down as president on November 20, 1924, and then returned to Sonora.

Calles became the next president, and in 1926 there was a change in the constitution to allow presidents to serve nonconsecutive terms. Obregón decided that he would like to contest the next election. In November 1927 Segura Vilchis, a Roman Catholic engineer, threw a bomb at Obregón's car at Chapultepec Park in Mexico City.

Obregón survived, but Vilchis and some accomplices were executed a few days later. In 1928 Obregón contested the presidential elections again— he was the only candidate—and won, although he was in bad health.

Returning to Mexico City to celebrate his victory, he survived an assassination attempt, but on July 17, 1928, at the La Bombilla restaurant in the capital, he was assassinated by José de León Toral, a Catholic seminary student who opposed the anticlerical policies of Obregón. He was arrested, tried, and subsequently executed.