|

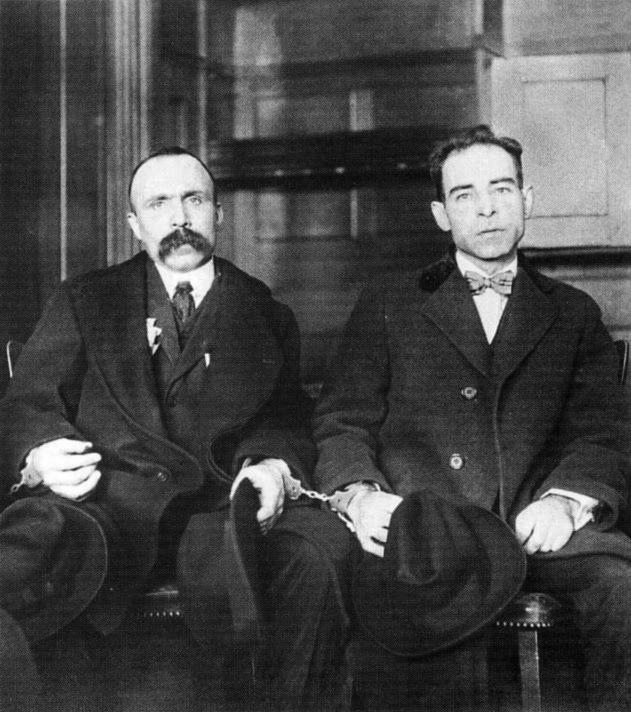

| Fernando (Nicola) Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzett |

Fernando (Nicola) Sacco (1891–1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (1888–1927) are best remembered as the victims of injustice following the wave of U.S. antiradical persecution in the years immediately following World War I.

Both men were Italian immigrants with revolutionary anarchist political beliefs. It is in the context of this political background that their legal difficulties began and led, it was claimed, to their prosecution. They were ultimately condemned to death for murder and executed by electric chair on August 23, 1927.

The circumstances behind their arrest, trial, and conviction were the gunshot murders on April 15, 1920, of Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli during the commission of a shoe factory payroll robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts.

|

Cash boxes containing $15,766.51 were taken, and a .32 Colt automatic pistol was the primary weapon used. Initially, the police linked the crime to an earlier robbery of December 1919 in Bridgewater, Massachusetts.

The U.S. political climate following the Russian Revolution and World War I produced a fear of radical subversion that became known as the Red Scare of 1919–20. Sacco and Vanzetti were followers of Luigi Galleani (1861–1931), a revolutionary anarchist who published the Cronaca Sovversiva. Galleani's writings promoted many forms of violent insurrection, including the use of bombs, terrorism, and assassination.

|

| Sacco and Vanzetti Protesters |

One member of this organization and an acquaintance of Sacco and Vanzetti, Carlo Valdinoci, was accidentally killed while attempting to bomb the Washington home of A. Mitchell Palmer

Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested on May 5, 1920, and were initially questioned about their radical activities. Although they denied such associations and the ownership of any guns, both had pistols and ammunition.

Sacco had a .32 Colt and Vanzetti had a revolver, which was of the same type as that taken from the guard at the time of the murder. This record of deceit helped create an atmosphere of suspicion that brought about their eventual linkage with the Braintree robbery.

Although both were tried for the 1919 South Bridgewater robbery, only Vanzetti was convicted, and he received a 15-year sentence. It was the May 21 murder trial that was to prove most controversial and serious. Both men claimed innocence and produced alibi witnesses, but the prosecution challenged their reliability.

It was, though, the possession of weapons that was their undoing, along with the negative trial atmosphere allowed by Judge Webster Thayer. The gun evidence from the .32 Colt in Sacco's possession ultimately convinced the jurors that it was the murder weapon. After a six-week trial Sacco and Vanzetti were found guilty of first degree murder and sentenced to death on July 14, 1921.

Their convictions marked the beginning of a lengthy legal struggle for an appeal and a new trial. In 1924 the defense's legal team was taken over by William Thompson, and the emphasis shifted from politics to one of fairness.

Motions were raised concerning bias, the defendants' and their witnesses' poor command of English, political intrigue, perjury, and illegal police activities. Many leading lights within the liberal and socialist set, such as Bertrand Russell

In 1925 a Portuguese immigrant, Celestino Madieros, confessed to the crime, which he claimed was part of the criminal activities of the well-known Morelli gang. But this confession failed to persuade the courts, and the death sentences were upheld. Sacco and Vanzetti went to their deaths on August 23, 1927.

The controversy over their innocence or guilt persists. In some quarters there remains the general notion that the Sacco and Vanzetti case produced a gigantic stain on the U.S. conscience and was a gross miscarriage of justice.

There are others who question this view. Insiders within the anarchist community years after the trial indicated that the pair was guilty but that the case offered a great propaganda opportunity that could be exploited. This group includes some whose claims exonerate Vanzetti but state that Sacco was guilty.

In 1927, 1961, and 1983 ballistics tests, making use of improved technology, have matched Sacco's gun to the murders. Most tellingly, there appeared in 2005 an Upton Sinclair