|

| U.S. Occupation of Japan |

The U.S.-led occupation of Japan began at 8:28 a.m. on August 28, 1945, when U.S. army colonel Charles P. Tench of General Douglas MacArthur's personal staff stepped out of a C-47 Dakota transport onto the battered runway of Atsugi Airfield outside Tokyo, becoming the first foreign conqueror of Japanese soil in its thousand-year history.

Tench and his crew were followed two days later by 4,000 men of the 11th Airborne Division. On the same day, the U.S. 6th Marine Division began landing troops at the Yokosuka Navy Base as U.S. and British ships steamed into Tokyo Bay and MacArthur himself put the seal on World War II victory and the beginning of postwar occupation by landing in his aircraft at Atsugi saying, "Melbourne to Tokyo was a long road, but this looks like the payoff."

The occupation was planned concurrently with the invasion of the Home Islands in early 1945 by MacArthur's headquarters. The occupation plan was to demilitarize Japan so that it would never again threaten its neighbors and to create a democratic and responsible government and a strong, self-sufficient economy. Operation Blacklist was designed to bring about a sudden surrender or collapse of the Japanese government, realized with the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The operation called for a three-phase military occupation of Japan and Korea, with 23 divisions and supporting naval and air forces. The first priority would be to secure bases of operation, control the Japanese government, disarm its military, and liberate 36,000 Allied prisoners of war and internees who were close to death from starvation, torture, and abuse.

The Japan that surrendered in 1945 was an exhausted, stunned, and starving nation. Having never known defeat or occupation in their history, the Japanese now saw their institutions destroyed, agriculture and industry wrecked, and 2 million countrymen dead. Acres of major cities were in ruins, thousands homeless, the emperor abject, and the armed forces defeated and dishonored. It was a complete collapse.

With Japan's surrender, MacArthur was appointed supreme commander for the Allied powers in Japan under a U.S. State Department directive entitled "United States Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan." Instead of Japan's being divided into separate nationally administered zones, as was done in Germany, the fallen empire would continue as one nation under its existing government and emperor, subject to U.S.-led direction.

|

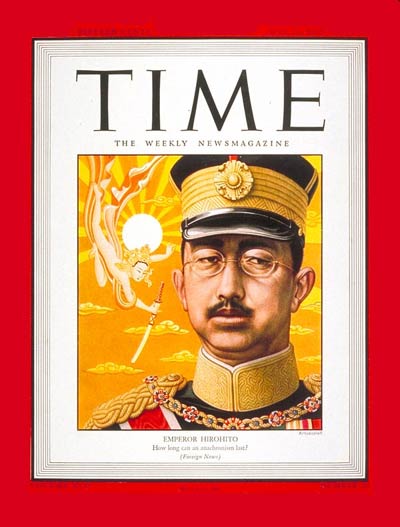

| General Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito |

Above MacArthur was the 11-nation Far Eastern Commission in Washington, established in December 1945, which was to make policy for the occupation and which could discuss and approve but not rescind previous U.S. decisions. Thus, in practice, despite Soviet complaints and demands for a share in the occupation, MacArthur had supreme power over Japan.

The first U.S. move after securing operating bases was to recover and repatriate prisoners from more than 140 camps across the Home Islands, airdropping supplies and sending out medical and transport teams to ring the survivors of Malaya and Bataan home. Nearly all of them were brought out by the end of 1945.

Meanwhile, some 250,000 occupying forces, including an Australian-led British Commonwealth occupation force of 36,000 Britons, Australians, New Zealanders, and Indians, fanned out across Japan. While the British force was assigned to southern Honshu and Shikoku Island (including Hiroshima), MacArthur banned Soviet troops from his occupation force.

With his headquarters at the Dai Ichi Building in Tokyo, MacArthur did not need to create a political structure to administer Japan. The nation's government was intact when it surrendered, so his directives were simply passed through his staff to the Japanese-established Central Liaison Office, which acted as intermediary between the occupation staff and the government ministries until the two groups developed working relationships.

After freeing the POWs, MacArthur moved to demobilize the battered Japanese war machine, whose 5.5 million soldiers, 1.5 million sailors, and 3.5 million civilian colonial overlords were still defending bypassed islands across the Pacific.

The Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy were converted into the First and Second Demobilization Bureaus, respectively, and administered the repatriation, disarming, and demobilization of these men. Most of this work was done by the Japanese under close Allied supervision.

Japanese warships, even the aircraft carrier Hosho, carried defeated troops home, making their final voyages before going to the scrap yard, where these ships were joined in destruction by tanks, kamikaze planes, midget submarines, and artillery shells of the once-mighty Japanese armed forces.

The United States also moved to break down the Japanese police state, decentralizing the police, releasing political prisoners, and abolishing the Home Ministry, which had controlled Japan's secret police agency, the Kempei Tai. With these changes in place, the United States was able by December 1945 to issue a Bill of Rights directive, which gave the Japanese U.S.-style civil liberties, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press.

The role of the emperor was also changed. Shortly after the surrender he met MacArthur, which enabled many Japanese to accept the new regime. In January 1946 Emperor Hirohito formally renounced his divinity, ending over a thousand years of Japanese tradition. He also began making public appearances in the style of Britain's royal family.

In April 1946 MacArthur ordered general elections as a referendum on the changes he planned. Three out of four Japanese went to the polls, including 14 million newly enfranchised women, to elect a free diet. The results supported a mildly liberal, prodemocracy government, an endorsement for his plans.

Next MacArthur directed the Japanese government to draft a constitution to replace the 1867 Meiji Constitution. While issued by the government in accordance with existing rules to change the constitution, this new document was drafted by MacArthur and his staff. It went into effect in May 1947.

The "MacArthur Constitution" created a parliamentary government, the Diet, with popularly elected upper and lower houses, a cabinet that held executive power, and a decentralized regional government of elected assemblies. The constitution also guaranteed basic freedoms.

Its most famous section was article nine, in which Japan forever repudiated war as a means of settling disputes and banned the maintenance of military forces. As a result, the modern Japanese armed services are called the Self-Defense Forces.

The United States also had to cope with a shattered economy. One-fourth of Japan's national wealth was lost to the war, prices had risen 20 times, and workers could barely afford to purchase what little food was for sale. Many people had to barter their possessions for fish.

MacArthur imposed numerous reforms on the Japanese economy. Believing that those who till the soil should own it, he had the Diet break up vast farms held by a few landlords. These farms were expropriated and sold cheaply to the former tenants.

MacArthur also worked to break up the commercial empires of the zaibatsu, or "money cliques," but this proved less successful. The large Japanese businesses were vital to the nation's economic rebuilding, and names like Matsushita,

Mitsubishi, Nissan, Honda, and Kawasaki, powerful before the war, remained so into the 21st century. Nevertheless, Japan's economy was rebuilt with speed and power.

MacArthur also rebuilt the Japanese education system by replacing nationalist curriculums and textbooks with more liberal materials, raising the school-leaving age, decentralizing the system, and replacing political indoctrination with U.S. and British ideals that supported independent thought.

MacArthur also liberated women by ending contract marriage, concubinage, and divorce laws that favored husbands. He also made high schools coeducational and opened 25 women's universities. The Japanese responded: 14,000 women became social workers, and 2,000 became police officers. Women filled up the colleges and new assemblies.

Changes wrought by the U.S. occupation were massive: Public health programs eliminated epidemics, U.S. police officials retrained Japanese policemen, and Japan's dull official radio programs of government speeches were replaced with a combination of public affairs shows, impartial newscasts, soap operas, and popular music, all of which attracted millions of listeners.

At the same time the Anglo-American presence in Japan did much to change Japanese society. The arrival of the occupation forces sent a shiver of fear through the Home Islands, fear that the dreaded gaijin—"hairy barbarians"—would rape, loot, and pillage, as Japanese soldiers had done in lands they conquered.

MacArthur gave strict orders regarding his troops' behavior but did not issue nonfraternization orders. As a result, U.S. soldiers were soon overcoming language barriers to play softball games against Japanese teams, playing tourist at Japan's many attractions, and giving out chewing gum and candy to ubiquitous Japanese children.

By 1947 the occupation had succeeded in its political and economic goals. Despite Soviet intransigence, Japanese society had been transformed. The combination of MacArthur's steely resolve, U.S. generosity, and Japanese industriousness and adaptability created the modern Japan, able to connect to both its historic roots and the Western world with its democratic values, economic systems, and advanced technology.

By March 1947 MacArthur himself said that the occupation was completed and began turning over control of the nation's affairs and policies to the Japanese. In 1951 the United States and most of its allies signed a peace treaty with Japan, ending an occupation that was generally conceded to have ended five years previously.