|

| SEASIA (Southeast Asia) |

The term Southeast Asia came to be used during

World War II, when the region was placed under the command of Lord Louis Mountbatten (1900–79). It includes the area to the east of the Indian subcontinent and to the south of China. In 2006 the countries of the region were Brunei, Cambodia, East Timor, Myanmar, Indonesia, Laos,

Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

In the first half of the 20th century, all of Southeast Asia except Thailand was under foreign domination. Southeast Asia is a region of ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and historical diversity. It has retained its own identity in spite of cultural influences from different areas.

The first half of the 20th century witnessed momentous events and new ideas that transformed the history of the region.

World War I, World War II, Japanese occupation, the rise of anticolonialism, the growth of communist ideas, and the onset of the cold war had varied impacts on the countries of the region.

In a geographical sense, before 1950 Southeast Asia comprised two broad groups. The mainland comprised the British colony of Myanmar (formerly Burma), the French colony of Indochina (Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam), and Thailand. Island Southeast Asia consisted of the British colony of Malaya, the

Netherlands East Indies, and the Philippines under U.S. domination.

Thailand survived without becoming a colony of either Britain or France due to the sagacious policies of the kings. It did not succumb to colonial subjugation by signing unequal treaties of friendship and commerce or allowing extraterritoriality rights to France, Great Britain, the United States, or Germany.

Rama V (1853–1910) maintained friendly relations with the colonial powers even at the cost of Thai territory.

King Vajiravudh (1881–1925) joined with Allied powers and was able to revoke extraterritorial rights. In 1932 there occurred for the first time in the history of Thailand a bloodless coup, which ended absolute monarchy there. Pridi Phanomyong (1900–83) and Pibul Songgram (1897–1964) were important leaders.

The military dominated the affairs of government. Thailand gave the Japanese passage to invade the British colony of Malay. But after the defeat of Japan, Thailand gave up the newly acquired territories to Malay, Burma, and Cambodia.

The British colony of Burma was governed as a province of British India until 1937. The Japanese drove out the British in 1942. Burmese nationalism, which had been given a boost after World War I, was in full swing. The days of the British were numbered. Leaders like Aung San (1915–47), who had collaborated with the Japanese, sided with Great Britain in 1945.

On January 4, 1948, the country became independent. The three Indochinese states of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam rebelled against French colonial rule.

Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969) had pleaded in vain with the Allied countries to give independence to the Indochinese countries at the Paris Peace Conference.

The Indochinese freedom struggle had communism as one of its ideologies for a sizable number of people. When the French came back again, the

Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), or North Vietnam, had already been established on September 2, 1945.

The Khmer Issarack, or the Free Khmers, of Son Ngoc Thanh (1907–76) and Souphanouvong's (1901–1995)

Pathet Lao (Land of Lao) had been aligned with the Vietminh. The First Indochina War began in 1946 and continued until the French defeat eight years later. The communist faction had not accepted the limited independence given to Laos, Cambodia, and South Vietnam in 1949.

The Philippines was annexed by the United States after the Spanish-American treaty in December 1898. After the Philippine-American War (1898–1901) military occupation was replaced by civilian governments. In principle, the independence of the Philippines was recognized by the U.S. Congress in the Jones Act of 1916.

On July 4, 1946, it got complete independence. British Malaya had three types of administration: Crown colonies, protected federated states, and protected unfederated states. The Japanese had faced tough opposition from the Malay Chinese, who had formed the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army.

The British created the Malayan Union in April 1946, which faced problems from the Malayan Communist Party. The pan-Malayan party called the United Malay National Organization was established in May of the same year. The British created the Federation of Malay in February 1948, which became a stepping stone to independence in 1957.

In World War II Japan occupied Singapore on February 15, 1942. General disillusionment with British rule and the growth of political consciousness accelerated. After the abolition of Straits Settlement,

Singapore became a separate Crown colony on April 1, 1946.

Elections to its legislative council were held in March 1948. The British government was compelled to give greater self-government to Singapore in 1953. Singapore attained self-government in 1959, with Britain retaining control of its defense and foreign affairs.

The Dutch established direct rule over the whole of modern Indonesia by 1909. Nationalism grew out of the country's glorious historical past, colonial exploitation,Western education, anticolonial movements in Asia, and miserable social conditions.

The first nationalist organization was Budi Utomo (Noble Conduct), founded in May 1908. The Sarekat Islam (Islamic Association), established in 1912, became a mass organization with membership running above 2 million. In 1920 a group of radicals formed the

Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI, Communist Party of Indonesia).

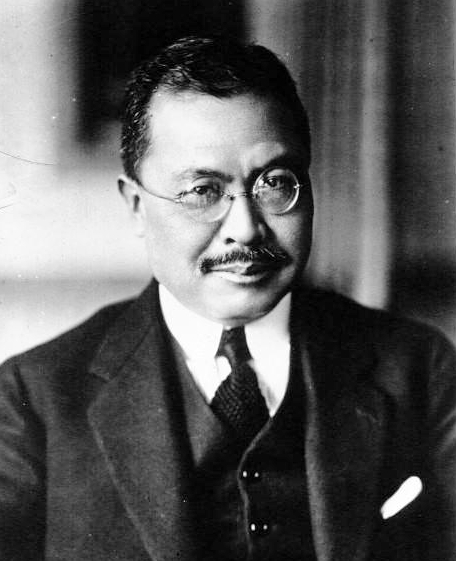

The Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI, Indonesian Nationalist Party), with its motto of one nation (Indonesia), people (Indonesian), and language (Bhasa Indonesia), was established in 1927. It was led by Sukarno (1901–70). The nationalist struggle was suppressed by policies of repression and by sending leaders to prison camps.

On August 17, 1945,

Sukarno and Muhammad Hatta (1902–80) proclaimed independence and established the Republic of Indonesia. But it took five years of guerrilla warfare and diplomatic offensives to establish its independence unchallenged, as the Dutch came back. At last, on August 17, 1950, the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia was restored.

In the second half of the 20th century this historical legacy, along with new developments, shaped Southeast Asia. In the 21st century Southeast Asian countries had increasing importance among the nations of the world.