|

| Soviet Union New Economic Policy Poster |

The New Economic Policy (NEP) was the transition from an inherent policy of "military communism" food surplus requisitioning to regular food taxation accompanied by liberalization of internal trade and a state monopoly on international trade and heavy industry.

The introduction of the NEP was the result of the necessity to maintain the rural population and the agricultural sector of the economy, which were exhausted by civil war. A famine in 1921–23 in the central part of Russia due to economic as well as ecological and climatic factors was an argument in favor of the revision of existing economic policy.

The NEP was an initiative of Vladimir Lenin, who, by the beginning of 1921, had already realized that the young Soviet state could face a peasants' war. The 10th congress of the Russian Communist Party (of Bolsheviks) took place in March 1921 and adopted Lenin's proposal to transition from food surplus requisitioning to a regular taxation system, the starting point of the NEP, called nepo or nep.

|

From the very beginning the NEP was perceived by Communists as a forced temporary deviation from the immediate introduction of communism based on so-called Marxist ideals.

Changes in the food taxation system (the transition from voluntaristic food requisitioning to regular food and, soon afterward, to money taxation) accompanied other reforms in the economic sphere. One of the most important of them was the introduction of the possibility for peasants to sell their surplus products at free markets, which meant the renewal of free internal trade in the country.

Foreign concessions and lease and privatization of small enterprises were allowed, and trusts got permission for their activity on self-supporting bases. The organization of new collective and state farms was temporarily suspended, and private land cultivation and land lease were allowed.

Nevertheless, the building of communism was not cancelled at all, and key aspects of the economy were totally controlled by the Soviet state. It was a sort of Bolsheviks' guarantee that in the future, socialist elements would overcome capitalist ones under the proletariat dictatorship.

The first results of the introduction of the NEP were visible as early as the 1925, when in most Soviet republics grain production was already as high as before World War I, and industry production levels were also renewed.

Changes in economic policy and a general improvement of human welfare were accompanied by general liberalization in the social and cultural spheres. The end of hunger and economic disaster destroyed the basis for peasants' rebellion movements and contributed greatly to the spontaneous breakup of widely distributed armed bands, particularly in the Ukraine.

Mass repressions were stopped, and amnesty was given to members of groups and noncommunist parties. Political emigrants were allowed to return to the country. Such liberalization, alongside an improvement in general welfare, gave the population under Bolshevik rule a desire for freedom and caused movement in social and cultural life, ethnic identification, national revival, and other processes noncoherent with proletariat dictatorship ideology.

In social and cultural spheres, signs of the end of the general liberalization of internal policy connected with the NEP appeared as early as 1926–28. Usually they are associated with the campaign against socalled nationalistic deviations in the Ukraine, which was a specific trend in the communist movement that tried to synthesize the building of communist society with national liberation movements. This campaign was accompanied by an attack on the Orthodox and Autocephal Churches and the destruction of monasteries and churches.

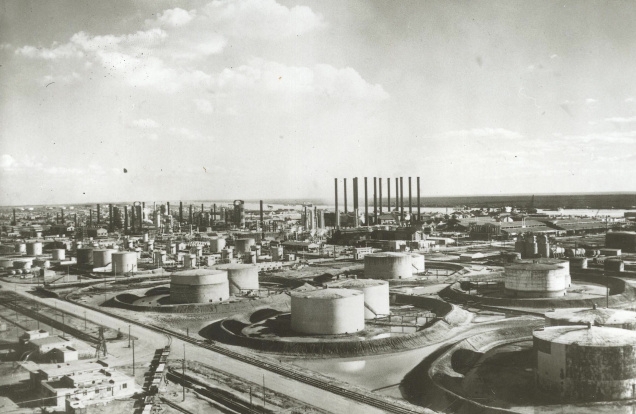

In spite of obvious traces of economic growth, the country remained mostly agrarian in its economic orientation and could hardly be competitive with the leading European countries in its struggle for survival. Since the very beginning, the Soviet state had been permanently preparing for the great war against the imperialists, so a well-equipped and modern army needed to be created and maintained.

One of the key tasks of the Bolsheviks, headed at that time by Joseph Stalin, became an acceleration of heavy industry development, which was ensured by significant investments. It was proclaimed the main goal of the country's development at the 14th congress in December 1925.

The only reliable source of such investments for the Soviet state was an internal one; that is, it could be maintained by redistribution of internal gross product, guaranteed by strictly controlling all spheres of the economy, the agrarian one included.

One means of such gross product redistribution—artificially created differences in prices for industrial and agricultural products, with the help of which up to half of the agricultural segment's income was cut in favor of the industrial one—was widely used during the NEP period. By 1926 it resulted in the so-called NEP crisis: Price control by the state caused a significant excess of demand.

Economic policy reorientation, which factually meant dismantling the New Economic Policy, was marked by two epochal decisions by Communist leaders: industrialization and collectivization strategy plans, which came to be known as the Great Breakdown.

The first five-year plan of industry development for 1928–33, adopted by the 15th congress of the Communist Party (December 1927), envisaged a high but relatively balanced rate of industry growth. Nevertheless, soon the Communist leadership demanded acceleration. Investment shortage was accompanied by a food crisis in 1928, which was caused by extremely poor harvests in the main Soviet granaries.

It was given as the reason to reactivate food requisitioning, to destroy the agrarian market, to intensify the organization of collective farms, and to begin a campaign against relatively prosperous peasants (kulaki), proclaimed by Stalin at the All-Union Conference of Marxists-Agrarians in December 1929.

These decisions faced economically motivated objections, and Stalin's ideas of economic strategic development met strong opposition among Communist Party leaders, including Nikolay Bukharin, Nikolay Rykov, and others. It was a reason that Stalin started his struggle for absolute power, which implied new waves of terror, hunger, and political repressions. In fact, dismantling of the New Economic Policy was the starting point for a final totalitarian regime in the Soviet Union.