|

| Japanese forces |

The Nationalist government in China faced two major challenges after completing the Northern Expedition in 1928: domestically, the Communist rebellion, and internationally, Japanese aggression. While warlords ruled China Japan could exploit Chinese disunity by extorting concessions.

Japanese militarists bent on preventing the formation of a strong China had tried and failed to halt the advance of the Nationalist Northern Expedition in May 1928 by landing troops in Shandong (Shantung). They failed again in December 1928 to prevent the young warlord of Manchuria from acceding to the Nationalist government.

The Manchurian incident demonstrated the ascendancy of Japanese militarists over the civilian government. On September 18, 1931, junior officers of the Kwantung Army (a unit of the Japanese army stationed in Manchuria, a Japanese sphere of influence) attacked many cities in Manchuria (called the Northeastern Provinces in China). China appealed to the League of Nations, which passed resolutions ordering Japan to halt its aggression, in vain.

The league then sent a commission of inquiry (the Lytton Commission) to investigate the legitimacy of the puppet government that Japan set up in Manchuria. When the commission report rejected Japanese claims and ordered Manchuria's rendition to China, Japan resigned from the league.

Emboldened by the league's impotence and the indifference of the United States, Japan stepped up its aggression against China. Its troops conquered Rehe (Jehol) province, which adjoined Manchuria, in 1933 and attacked the Inner Mongolian provinces in 1934.

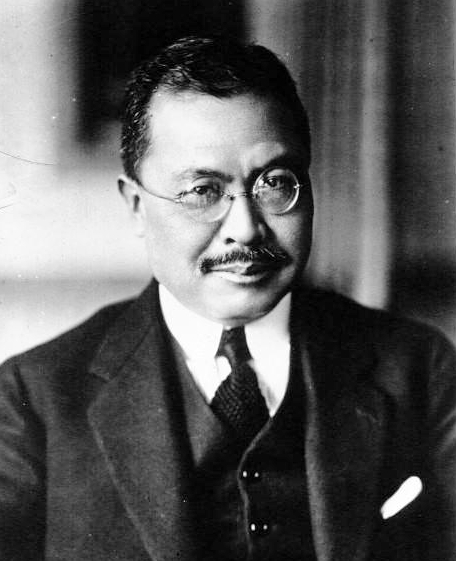

Fearing an all-out war where it would be crushed and beset by the Communist rebellion, the Nationalist government, led by

Chiang Kai-shek, sought piecemeal resistance and negotiations with Japan in order to buy time to build up Chinese infrastructure and defenses.

|

| Japanese troops marching through the rubble of a village near Hankow |

Successes against China made the Japanese militarists heroes at home, and their tactic of assassinating their opponents silenced the opposition. Their avowed policy was to control all of China, then move by sea to conquer South and Southeast Asia and by land to conquer the Soviet Far East and then all of Central Asia.

These ambitions would lead to the formation of an Axis between Japan, Nazi Germany, and Fascist Italy in 1938 that aimed at world domination by these three nations. In 1935 Japan initiated a program to create another puppet state, called North Chinaland, to include five provinces in northern China.

The acceleration of Japanese aggression led to widespread demand in China that all Chinese unite and that the government cease its anti-Communist campaigns. In response to that prospect, Japan initiated the Marco Polo Bridge incident on July 7, 1937, by attacking a town in northern China at a railway junction near the

Marco Polo Bridge (called Lukouchiao or Lugouqiao in Chinese).

|

| Chiang Kai-shek |

Realizing that the incident was part of a large design, the Chinese government decided to resist to the end. A United Front was formed with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and other parties and groups, all pledged to support the war of resistance led by the Kuomintang (KMT). Japan had expected to conquer China in three months. The war would last eight years and become part of World War II in Asia.

China Fights Alone

The modern Japanese army, aided by air and sea power, inflicted heavy losses and conquered the entire coastal region by the end of 1938. However, Japanese attempts to destroy Chinese morale by bombing schools, destroying industries, and treating the civilians in conquered areas with extreme brutality only forged an iron will among the Chinese to fight on.

The rape of Nanjing (Nanking), in which the Japanese soldiers raped, tortured, and slaughtered upward of 300,000 Chinese in the surrendered former capital, was one of the most despicable acts of brutality in

World War II.

|

| Chinese Kuomintang troops fighting Japanese troops |

Millions of Chinese civilians were killed in the war, but more millions trekked to Free China in the interior, moving schools, libraries, and factories to continue resistance. To slow the Japanese advance, in 1938 the Chinese even breached the Yellow River dikes, at a horrendous toll to the local population.

The Chinese government moved too, up the Yangtze (Yangzi) River first to Wuhan and finally to Chongqing (Chungking) in Szechuan (Sichuan) Province, deep in the interior, where the mechanized Japanese military could not penetrate, though its bombs did inflict heavy damage.

Chongqing was repeatedly destroyed by Japanese incendiary bombs, but life and factory production continued in caves excavated in the surrounding mountains, which served as air-raid shelters. Despite great odds, the government persisted in its goal of resistance combined with reconstruction.

China fought alone with little outside aid until Japan attacked

Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Japan could not entice prominent Chinese leaders to collaborate. The only man of national prominence to defect and form a quisling regime was Wang Jingwei (Wang Ching-wei) in 1938.

But he had become so discredited by then because of his previous political machinations and because Japan so obviously dominated the several puppet regimes in China that few followed him.

The United Front with the Communists was ill fated and a lifesaver for the besieged remnant Communist forces, down to about 30,000 men in 1937. From the beginning the CCP used it to increase their numbers and territory, while the KMT army was mauled by superior Japanese forces.

|

| Chinese troops marching on The Great Wall |

As Communist leader Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung) told his men, "Our fixed policy should be 70 percent expansion, 20 percent dealing with the Kuomintang, and 10 percent resisting Japan." In the light of these policies, it is not surprising that even nominal cooperation between the two parties had broken down by 1941.

In April 1941 Japan and the

Soviet Union signed a neutrality pact that allowed the Soviet Union to focus on preparing for war against Germany. This pact also removed the doctrinal basis for CCP-KMT cooperation. Their standoff continued throughout the war.

The CCP continued its expansion, and the KMT maintained a military blockade of CCPcontrolled areas around its capital, Yanan (Yenan). The war also provided the CCP an opportunity to restructure its party and its army and provided Mao and other leaders time to develop new social, political, and economic institutions and strategies.

China Gains Allies in World War II

China fought alone between 1937 and 1941 except for Soviet aid in its air defenses in the initial years, some small loans from the United States and Great Britain, and an Air Volunteer Corps (Flying Tigers) of U.S. airmen under General Claire Chennault. After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and British and Dutch colonies in Asia in December 1941, World War II expanded to include all Axis powers against China and all Allies against Japan.

|

| Chinese Communist troops training with American Thompson sub-machine guns |

China became part of the China-Burma-India theater of war, and Chiang Kai-shek became supreme commander of the China theater. China also began to receive expanded U.S. aid. 1942 was a bleak year for the Allies in Asia as Japan conquered most Western holdings—the Philippines,

Hong Kong,

Singapore, Malaya, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies.

In contrast, China had stood alone against Japan for over four years. China's international prestige soared. In 1943 treaties were signed between China and the United States and Great Britain that ended 100 years of unequal treaties.

Chiang and Madame Chiang Kaishek traveled to Cairo, Egypt, to meet with British leader Winston Churchill and U.S. president

Franklin D. Roosevelt. The leaders agreed that Japan would have to surrender unconditionally, return its conquests since 1895 to China, and grant Korea independence.

War also brought disagreements between the Allies. Churchill and Roosevelt had agreed that they would give first priority to defeating the Nazis in Europe, then the Japanese in the Pacific, with the Chinese theater coming third.

Friction developed between China and its allies over expectations. In exchange for China's receiving U.S. Lend-Lease aid, the United States expected China to expand its role in the war, while exhausted China expected the United States to bear a greater burden in the fighting. There were also disputes over Lend-Lease.

Roosevelt appointed newly promoted general Joseph Stilwell, the chief of U.S. forces in China, Chiang's U.S. chief of staff, and gave him control over Lend-Lease materiel in China (whereas Lend-Lease materiel in Britain was under British control). China was also disappointed that it received the least amount of Lend-Lease, although the logistics of transportation were a factor in the limited amount reaching China.

The worst thorn in the side of Sino-U.S. relations was Stilwell's abrasive personality, for which he was called Vinegar Joe and his insulting attitude toward the Chinese leaders. Stilwell also clashed with Claire Chennault, an advocate of air power, and finally demanded that he be handed total command of Chinese troops.

Convinced that Stilwell's goal was to subordinate rather than cooperate with the Chinese, Chiang demanded his recall, which was endorsed by General Patrick Hurley (secretary of war under President Hoover), Roosevelt's special emissary to China to mediate between Stilwell and Chiang.

He was recalled in October 1944 and replaced by General Albert Wedemeyer, who was not given command of Chinese troops. Relations between the two nations improved as a result. Hurley, however, was unsuccessful in mediating between the KMT and the CCP.

In February 1945 Roosevelt met with Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin at Yalta to obtain Soviet entry into the war against Japan after Germany's surrender. The terms included important concessions to the Soviet Union in Manchuria and Chinese recognition of the independence of Mongolia (a Chinese possession that had become the first Soviet satellite state in 1924).

These agreements were made without prior consultation with the Chinese government, which was forced to agree. World War II ended in Asia on August 10, 1945, after the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on Japan.

China was Japan's first victim and had suffered most from Japanese aggression. The Chinese rejoiced in their victory, and in China's new international status as one of the Big Four Powers, a founding nation of

the United Nations (UN), and a permanent member of the UN Security Council.